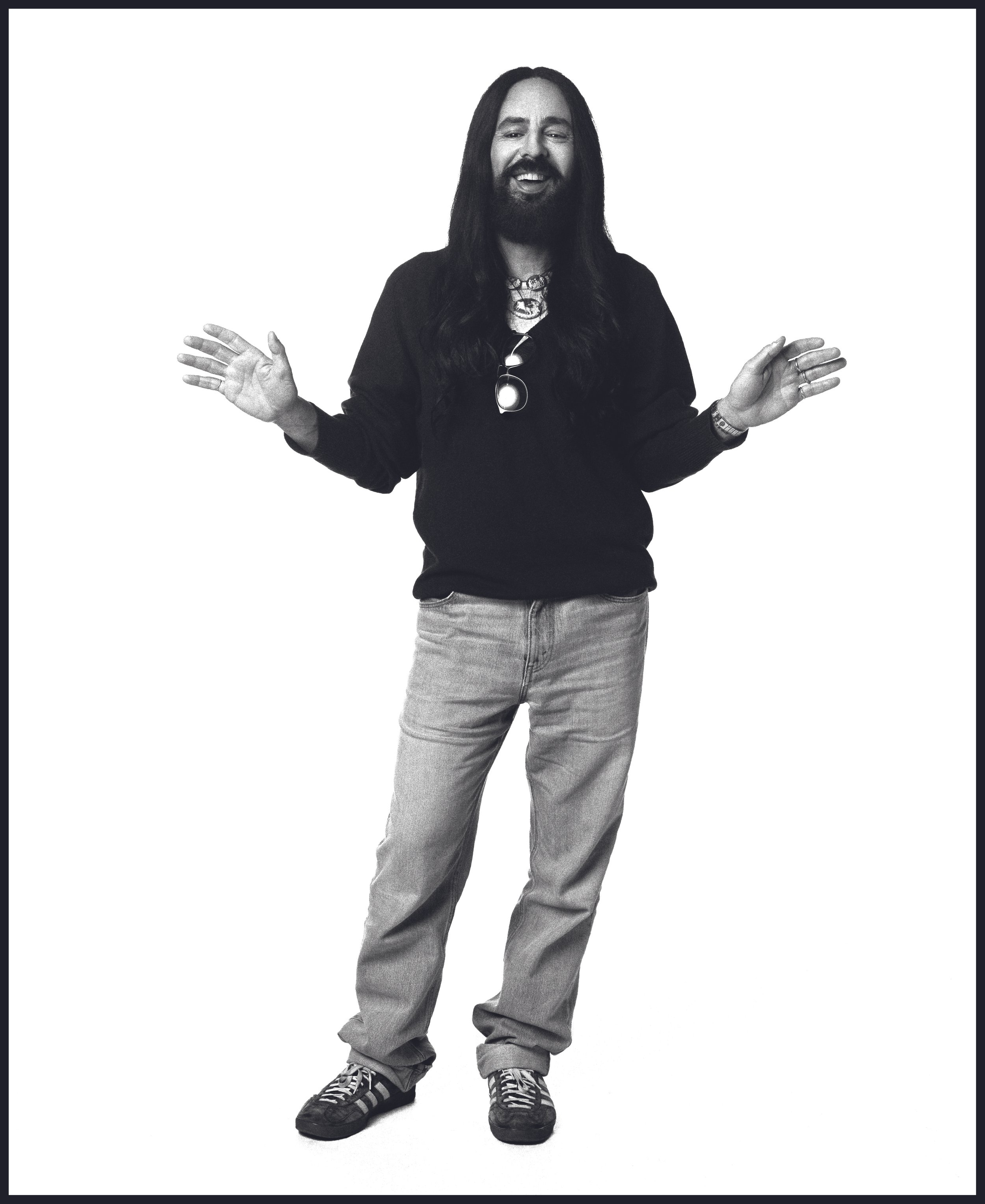

Exclusive Alessandro Michele Interview With Murray Healy For Perfect Issue 6.

Alessandro Michele Photographed by David Bailey

Since parting company with Gucci at the end of 2022, Alessandro Michele has put his unique talent for taking design history and making it contemporary to good use, working on the renovation of his fairy-tale home in Rome. But the question on everybody’s lips is: ‘Alessandro, what is your next job?’

Alessandro Michele has just arrived from David Bailey’s studio, and in a few moments will share his thoughts on the encounter, on the profound connection with history he felt upon meeting the photographer. ‘I mean, he photographed Mother Teresa and the Queen,’ he will observe, in a deferential near-whisper. Bailey immediately put the designer in mind of another fashion legend who had met so many totemic figures from the past: Karl Lagerfeld, with whom Michele worked in the early Nineties at Fendi.

But first, before he has even taken off his ankle-length oversized overcoat, Michele wanders over to the window and gasps at the view it offers. We are in a room on the ninth floor of The Standard Hotel, where a curved outer wall made entirely of glass commands a full 180-degree view over Central London. He immediately pulls out an iPhone from his coat pocket and starts taking photos of the jigsaw puzzle of architectural history spread about before us, tall cranes signalling where new pieces are being slotted in. The city’s past, present and future squeezed together: boxy Sixties office blocks and elegant 18th-century church spires; the stepped roof of Google’s brand new headquarters, still under construction, tapping on the shoulder of Kings Cross station, with its familiar twin arched windows dating from the 1850s.

More than fashion, it is architecture that has been on Michele’s mind in the 13 months since his surprise departure from Gucci. His free time has allowed him to focus on finishing a four-year renovation of his apartment in Rome. Situated near the Pantheon within the Palazzo Scapucci, his home is a hotchpotch of architectural styles, with some parts dating as far back as 800 years, old enough to be the stuff of fairy tales. It has a tower reputed to be the site of a holy miracle when a baby was saved from the clutches of a jealous monkey in the 16th century, which is why a statue of the Virgin Mary has looked out from its apex ever since. ‘Most of the space is Renaissance,’ says Michele, ‘but also there is early Baroque, and then some 18th century decoration around the windows. I like the mix and match of different patterns. It’s eclectic, it’s beautiful; you feel the traces of different eras.’

Bringing the place back to life has been a protracted process. ‘As with every historical building in Rome, there are so many rules, and it was in really bad condition. Working on something so old, you have to take care: you have to imagine your own life there while being respectful of the life that belongs to the place. Because it has a kind of soul, you know.’ The first year was spent stripping out unsympathetic additions introduced during the 20th century. ‘And the more we removed these layers and layers, the more the house started to look at us, the original soul of the house. It is like building a house in reverse.’ He unearthed treasures from the past: paintings and carved wooden ceilings from the early Renaissance; bricked-up windows, which he reinstated. ‘It seems like the house started to breathe again.’

This is by no means his first renovation project. ‘I started buying houses when I was pretty young. I’ve done this six or seven times: in Florence, in Rome, in the countryside.’ Right now he is still working on two houses in a small medieval village on top of a hill, about a 90-minute drive out into the country to the north of Rome. He has plans to open artists’ studios there; it’s a huge project, maybe a life-long commitment. He loves living in old buildings, he says, because it allows him to touch the many lives that have preceded him in those spaces. ‘So you can live more than your own life. It’s you plus other things: other voices, other presences. And that’s beautiful.’

His passion for saving old buildings isn’t driven only by aesthetics, but by practical and ethical considerations too. ‘We have so many old empty spaces that it doesn’t make sense to build something new. And if you do want to do something new, it’s very contemporary to rework with a new attitude a building that is old or abandoned. To preserve in this way is something that belongs to our era.’ He could of course be talking about fashion here: not only the way he reinvigorated the century-old house of Gucci, but the characteristic manner in which he processed the very idea of ‘history’ when creating his collections. There was no sense of nostalgia, no sense that the past is another country that we are separated from, in his approach. Instead he looked at all of fashion history as though it were something vital and integral to the present moment. He gazed on the past with the adolescent wonder of an art student whose mind has been blown by seeing an Old Master for the first time. That a work of art might be ancient is irrelevant: to fresh eyes and an open mind, in that first encounter it is brand new. This mindset is maybe what enabled Michele to make dress codes historically associated with fusty middle-aged respectability – voluminous, buttoned-up maxidresses; brown corduroy suits – look young and vibrant, even daring.

‘If you look outside here,’ continues Michele, beckoning through the wall of glass to London laid out beyond, ‘it’s a fruit salad of everything. You can’t consider the city from just one point of view; it’s not human. It’s like you,’ he says, nodding towards me. ‘You are not just here, chatting with me; you’ve been a kid and whatever, you have so many layers that you keep inside your person.’ A human being, like an old building or an old city, is a fruit salad of constructs and influences from across time, and demands to be understood according to its juicy, multifaceted complexity. ‘I think it’s not contemporary, the idea of keeping just one point of view.’

Acknowledging these layers of history hasn’t always been popular, in architecture or fashion. The 20th century, and especially its second half, was dominated by the idea of modernity, of a new world cut free from the baggage of the past. You can see why, after the horrors of the Second World War, artists, designers and architects sought to start afresh aesthetically. ‘The past was really heavy,’ says Michele. ‘So I totally understand. That was brilliant, you know, to imagine something that was not the past.’ But as humans we cannot detach ourselves from history. He gestures again across the landscape of London, which, after sustaining heavy bomb damage in the war, was nearly levelled and rebuilt in a more efficient manner. Instead, we ended up with new bits built in the gaps between the old buildings in a way that doesn’t really make sense. ‘It is a mess,’ says Michele, ‘but it’s so perfect. You wouldn’t want to change anything. It’s alive.’

He thinks there was a time, not so long ago, when a desire for modernity exercised a similar grip on fashion. Designers, charged with creating the future, couldn’t admit that they loved the past, he says, ‘otherwise you risk to be considered not a real designer’. He never had any such hesitation in expressing his love of history, though. ‘I’m lucky – I feel so much the present, because I appreciate that the past is here with me and it’s now.’ So understanding the past is what allows him to fully understand the present? ‘Yes. Because it is here, you know? It surrounds us in every single moment.’

He makes history sound like The Force in Star Wars; certainly the unique way he channelled it was his Jedi superpower at Gucci. And if you want to extend that analogy even further, there is indeed something of the mystic in his quiet, contemplative manner, in his penchant for metaphysical speculation, even in his long hair and beard and ageless sense of wonder at the world.

‘If you want to do something new, it’s very contemporary to rework an old building with a new attitude. To preserve in this way is something that belongs to our era’

For Alessandro Michele, Rome, like London, is a glorious mess. He was born and grew up there, but admits that it was only in adult life after time away that he learned to fully appreciate the city. ‘When I came back I was like, oh, this is a mess, I can’t live here. But then I started to think that while the mess is a lot, it’s also full of life.’ Now he loves Rome. ‘After so many years, now that I’m 50, I think there is something very deep that keeps me connected to the city. It is a very intense way to live, in the middle of this, like, cake, this unbelievably old cake, with layers and layers.’ Sometimes the sheer ancientness of the Eternal City can make it feel indifferent, so small are our lifespans in comparison to its millennia of history. ‘It’s like you feel nothing, so you really need to enjoy your life. Like spending two hours sitting outside a coffee shop, just chatting and waiting for a ray of sunshine.’

He doesn’t consider his own character to be particularly Roman, lacking the extrovert directness he sees in those around him, but he’s working on it. ‘I’m trying to change myself, trying to be more wild.’ It’s already happening, he notes, as he is absorbed into the city’s customs. ‘I feel myself really wild, because now that I’m not working, I’m spending more time in Rome. I mean, I can’t wait to go outside and take a cappuccino for, like, four hours.’ So he finally has time to relax and enjoy himself? By way of an answer, he lets out a long, deep sigh of satisfaction, like the hiss of a steam train that has finally come to a stop after a long journey.

It must come as a relief, after 20 years of living to the demands of the fashion calendar, I say. ‘Yeah. Yeah.’ From the café terrace he will watch the people come and go in a manner unique to the city. ‘There is a very strange relation between the people, the way they approach one another in the street. They ask the most intimate things of you. Like now, for example, they stop me in the street and ask, “Can I ask you something that I would really love to know? What will be your next job?”’

This of course is the million-euro question, or however much a creative director’s contract at a luxury house is worth these days. Everyone is waiting to see where Michele will work his magic next. I ask him what his answer is but he seems not to notice, commenting that the question these strangers put to him – ‘What will be your next job?’ – is a matter one discusses with one’s lawyer. Later I will send him a few questions by email to follow up our conversation, and some of them elaborate on this subject. Are you surprised that people on the street in Rome are so interested in what your next job might be? ‘Yes, I am a bit surprised, but evidently, it was a true and sincere love from both sides.’

Do you pay any attention to news about other designers joining fashion houses? ‘Not really.’

Are you able to say whether you have come to any decisions yet about where your next chapter in fashion might take you? ‘No, I am not able to say anything.’

By the time you read this, perhaps we will have an answer. But right now this is still a matter for his lawyer and for the future.

For now, back to our conversation about his love affair with Rome. Could he ever see himself living anywhere else? ‘Yeah!’ Michele declares, suddenly animated. ‘I like my city; I feel connected. But I like myself also, because I’ve lived in so many cities.’ Connected to Rome, then, but not bound to it.

Happily embedded in his apartment in the Palazzo Scapucci, the city remains home, for now at least. Where in its many rooms does he find himself spending the most time? He says he’s particularly fond of a high-backed chair positioned by his four-poster bed: ‘It seems like it is waiting for me every day.’ He’ll devote a good hour and a half every day sitting in that chair reading. ‘I really care about reading; that’s why I like this space.’ He also spends a lot of time in the dining room, ‘because it’s close to the kitchen and full of life.’ After meals, he tends to stay at the dining table. ‘And when friends come to the house, we stay there chatting. We are Italian: chatting around food and drink is very close to our life.’ There’s also his studio, the final part of the renovation; until recently that room served as a storage space while his builders got busy elsewhere. ‘I’m still working on the studio; now it’s starting to become a place. Maybe that side of the house is going to be more alive.’

So the renovation isn’t completely finished, then? ‘It’s never finished for me. You should always keep things ongoing. Because you feel alive, and you feel the house alive too. It is breathing with you, it is growing.’