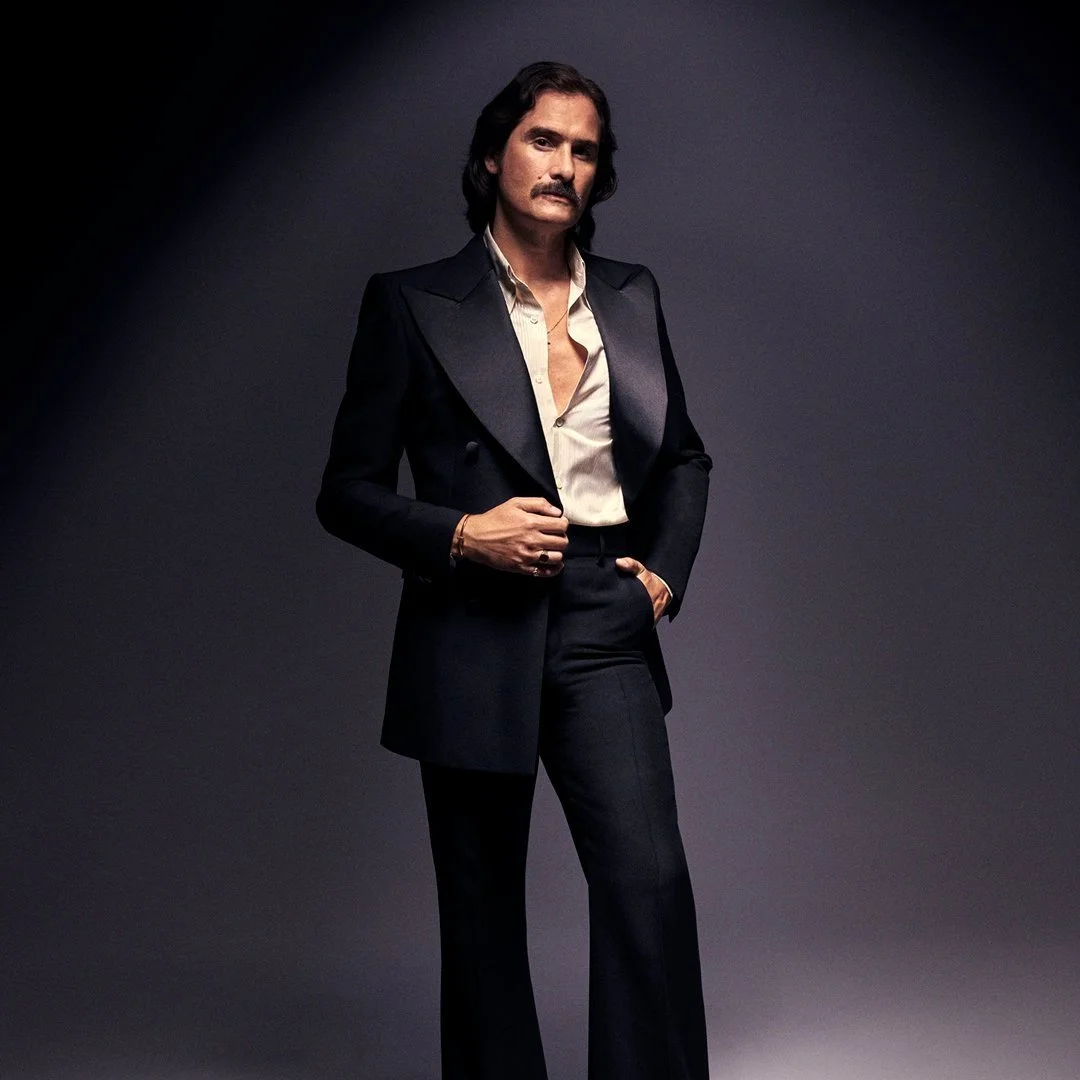

Glenn Martens.

Glenn Martens is having a good week: he’s back home, finally, in his Paris apartment. ‘So I’m extremely happy,’ he says, grinning as he rolls a cigarette which he then puffs on contentedly. ‘I’ve rediscovered my sofa, my kitchen.’ Behind him in the Zoom window I can make out a decorative fireplace, maybe 19th century, and an antique rug hanging on the wall. He’s barely spent any time here since becoming the creative director of Diesel, whose headquarters are in Breganze, a small town about an hour’s drive inland from Venice. Now he’s home for a decent 10-day stretch – his first extended visit in over a year, although this isn’t a holiday. He still has work commitments in Paris – there’s Y/Project, the French label he has headed up for nine years, and his couture collection as a guest designer for Jean Paul Gaultier to finish. But today, working from home, the agenda is all Diesel.

Announced in October 2020, what made Martens’ appointment at Diesel so exciting was that he was not an obvious candidate, as on the face of it the worlds of Y/Project and Diesel couldn’t be further apart. The ubiquity, utilitarianism and relative affordability of the Italian denim-focused lifestyle brand, which boasts over 400 stores and 5,000 points of sale worldwide, is a far cry from the niche appeal of Y/Project, the high-end luxury label where Martens became creative director following the death of its founder Johan Serafty in 2013. Since then Martens has made the label his own, expanding it to include womenswear, pushing its ethos of high-concept creativity (he has previously commented, ‘It’s not about being beautiful, it’s about seeing how far we can go’) while grounding it in a recognisably streetwear-y sensibility. So while the garments are reassuringly familiar – jeans, T-shirts, tracksuits, slip dresses – how you get into some of them can be less straightforward: a variety of twisting seams, asymmetric fastenings and eccentric openings that might equally accommodate a neck, an arm or a leg offer multiple ways of wearing them. Martens has acknowledged that Y/Project is a group effort, crediting the design team he works with there, but it’s not hard to see how much of his own creative personality is instilled in its collections. You only have to look back a decade to when his own-name label featured on the Paris Fashion Week schedule – take, for example, his cable-knit dress for autumn 2012, which featured a second neck hole positioned over the small of the back. There’s a conceptual consistency that runs all the way through to the cable-knit pullover that opened Y/Project’s show for spring 2022, where the cables divide and intertwine at the top to form at least three possible neck holes.

The contrast between Y/Project and Diesel actually serves both brands’ best interests, Martens notes, as well as his own sanity. ‘I don’t have a conflict of interest between the two – they’re both different brands with different types of creativity. So I’m not becoming this psychopath person who doesn’t know what he’s doing for which company. That can happen! If both brands are too close to each other, you stop knowing where one ends and the other begins.’

But while the two labels differ markedly in scale, audience and creative process, he reckons there is some crossover. ‘I think the fundamental values of Diesel are quite similar to Y/Project in so far as it’s really about having fun and enjoying life and not taking itself too seriously at all.’ If Y/Project trades on Martens’ reputation as a graduate of the Antwerp School – a tradition to which the words ‘tricksy’ and ‘conceptual’ will be forever welded, and to which ‘fun’ is more seldom applied – he also undercuts it with a light touch of absurdist humour which runs through his label. ‘I think both of the brands very much have this as a connection point.’

Martens’ journey to Diesel began in 2017 at the ANDAM Awards, the annual honours handed out by France’s National Association for the Development of the Fashion Arts, where Martens won the grand prize of €280,000 for his work on Y/Project. Diesel’s founder Renzo Rosso is a member of the ANDAM jury. ‘That’s where the conversation started,’ says Martens. ‘I think he really likes what I did at Y/Project. We started chit-chatting and he came to the studio.’ There was some discussion about the contemporary fashion landscape generally and Diesel’s ready to wear in particular. ‘But I wasn’t really interested in taking care of that.’ Then Rosso invited Martens to be a guest designer on Diesel’s designer collab line, Red Tag, for its second season. Rosso appeared pleased with the result: ‘I think he had really good feedback!’ When the conversation returned to what Martens might do for Diesel in a more long-term capacity, the scope of his potential role widened. ‘It was not only about ready to wear, it was about the whole company: every single licensee, every single product category. That’s where it really started becoming more interesting for me, because that’s when you can really do something to change the perception of the brand.’

The context of when this conversation was taking place – spring 2020 – had focused Martens’ thoughts on the next stage of his career. ‘It was the whole confinement with Covid, where we’re all locked up at home, and we’re all a bit like, OK, what’s the whole point? You have time for reflection, basically. You rethink everything you’re doing. And for 10 years I’d been doing Y/Project, egocentrically designing around what I want to do as an artistic person. It was really about me, me, me and my creative world. I was thinking, at 38, is this all I want to be doing?’ Other conversations were going on at the same time, between Martens and the owners of brands where the designer might have seemed a more obvious fit. ‘I was definitely talking to luxury houses also during the pandemic. And even though I love all the luxury houses and I think they’re beautiful and gorgeous, at the end of the day the exercise is the same as with Y/Project: to make really creative, beautiful clothes which are extremely expensive, talking to only a certain type of client which is very much more committed to the luxury concept. Whereas at Diesel it’s much more real… It’s reality, it’s not only the dream.’ Not that he has any problem with fashion’s more fantastical side. ‘I LOVE the dream! We make beautiful things that nobody needs, and I think that’s great; that’s why I’m doing Jean Paul Gaultier couture now. But of course in fashion there’s more than that. There’s also the need of being dressed and the need of surviving; of getting a great pair of jeans because you have to go to work.’

In addition to its utilitarian raîson d’être, what made Diesel appealing was its vast reach. ‘It has so much more power in the way it talks to so many more people. We’re not only talking to the elite; every single person is potentially a Diesel person. It doesn’t matter what background you have, how much money you make, what your social status is, your sexuality. That’s what convinced me that this was definitely the direction I wanted to go in as a second chapter to my career.’

He arrived at Diesel with no specific objective or brief. ‘That’s actually one of the most amazing things about this company, that no one was there to tell me what to do!’ He laughs. ‘Of course, that’s also destabilising in a way – you’re a designer coming from luxury, and suddenly there’s this huge train going at 360 km/h, and you have to jump on it and decide where it’s going and try to redirect it while it’s still going at 360 km/h.’

The runaway train already had several scheduled stops that Martens had to negotiate. One of his first tasks was to design pop-up stores planned for Amsterdam and Washington DC. ‘On day two, the architect is like, “We need a concept.”’ Martens’ solution was to paint the interiors in that hot-blooded Diesel shade of bright red, with the logo projected in massive white letters four metres high. ‘It’s supposed to be temporary but I was quite happy with it, because my first job here is to reconnect to the founding values.’ This was the first indication of how Diesel’s new creative director intended to embrace its past. ‘It’s definitely logomania, like Diesel bringing Diesel back – but in a fun, unexpected way, not taking itself too seriously.’

His next task was to design a statement trainer. ‘Sneakers have always had a very big turnover at Diesel. People who want to buy denim also want a sneaker to go with it as part of a total look. And if we want to be in the sneaker business, I felt we need a hero sneaker, something which screams a bit louder but also reconnects with the DNA of the brand.’ The result is the Prototype, a chunky shoe with a tyre-tread texture that sweeps up off the sole to cover the foot. Martens relished designing it; he’d never had the opportunity before, he explains, because trainers require massive minimum production orders on a scale incompatible with Y/Project’s niche appeal. He’s very happy with it – ‘I think it’s a sexy shoe’ – and he got his first inkling that the design had struck the right chord when he wore a pair on the shoot for Diesel’s spring/summer 2022 film. ‘All the models were going mental, asking “When are they coming in the stores?!”

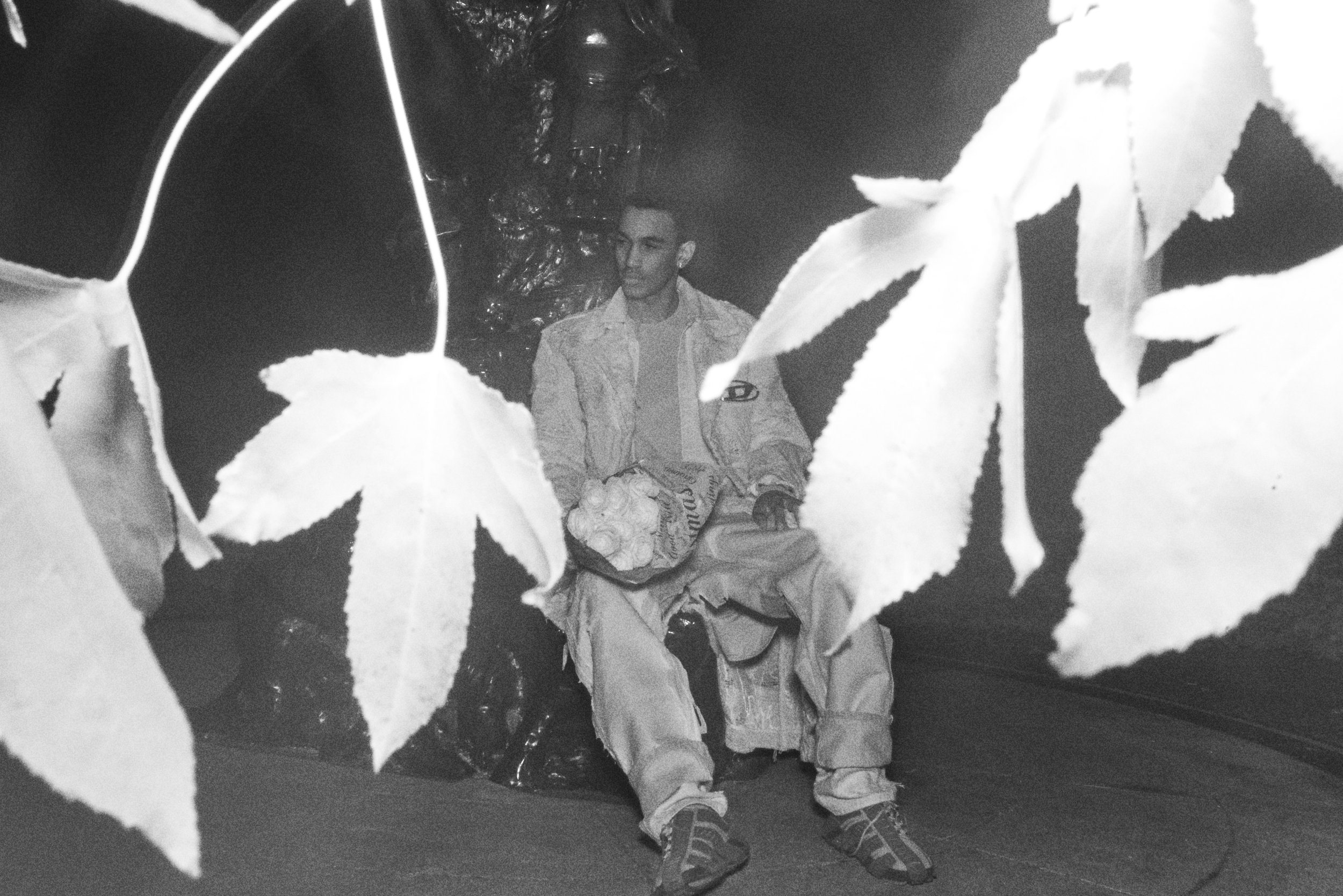

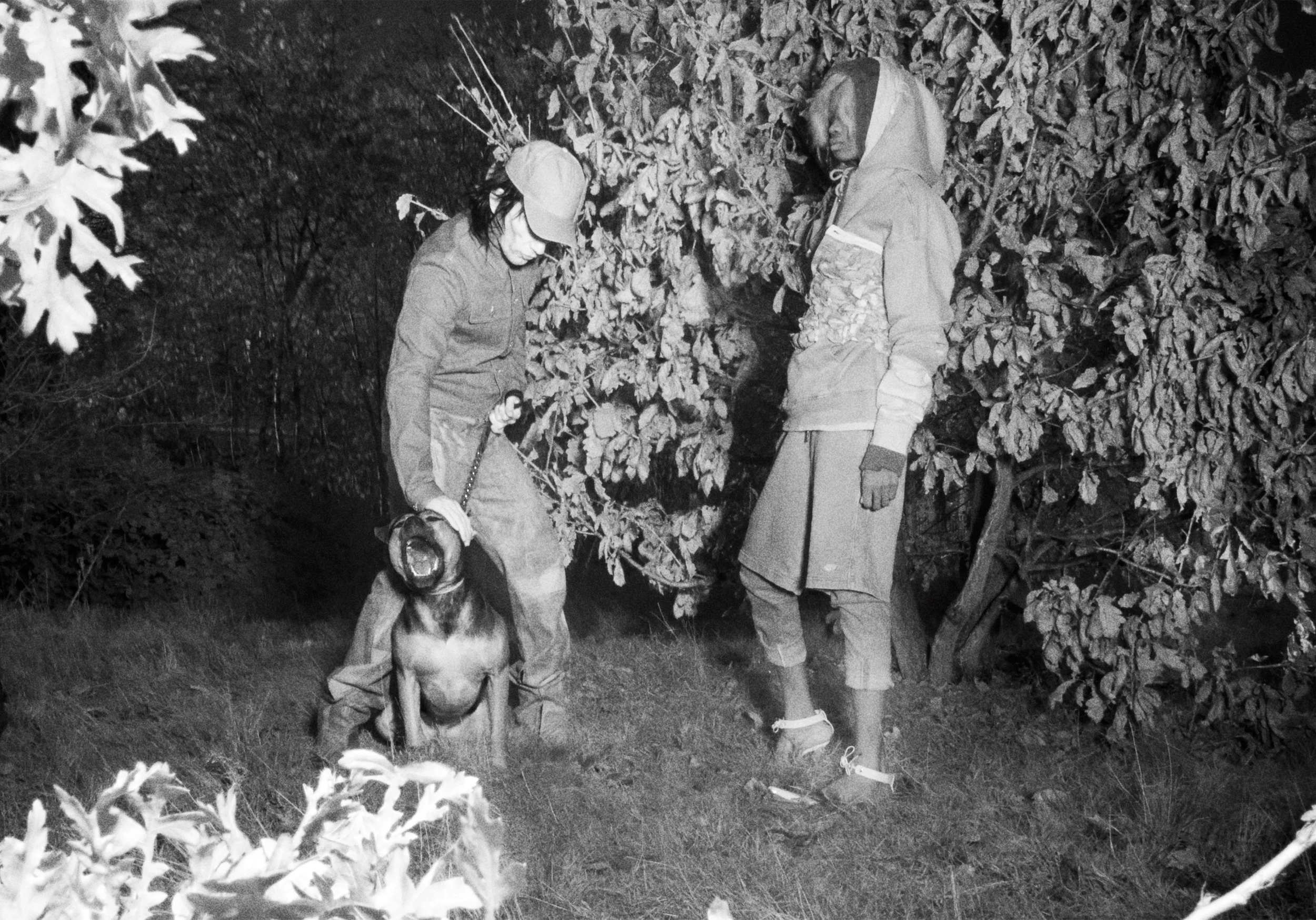

Created in lieu of the spring 2022 catwalk show, the film presents the collection within a vision streamed from the consciousness of New York model Ella Snyder, her hair dyed Diesel red. Featuring kids enjoying themselves on the dancefloor and through the labyrinthine corridors of a basement club before venturing out onto the street and eventually to another world, it showcases looks that smartly processes the brand’s past glories for the present day, offering a hedonistic vision of the near future for younger audiences, a vivid acid flashback for older ones who partied through Diesel’s previous heyday at the turn of the millennium. Back then Diesel enjoyed an enviable status for a mass-market label, maintaining a broad appeal that cut across a variety of fashion and style divides. The fashion landscape was very different then, with brands at either end of the market struggling to appear relevant. In the middle of it all, Diesel confidently maintained a cross-market currency, selling a youth lifestyle at a price that made it premium without being completely unaffordable. Distressed and washed to make them look authentically worn in, Diesel’s jeans seemed to satisfy even the fussiest customers, from specialist denim purists who might otherwise only wear rare deadstock Levi’s, to wealthy Bond Street types usually averse to mass-market brands seduced by the quality of its denim fabrications and cuts. Diesel’s clothes anticipated the zeitgeist too, tinged with a retro Euro chic that nodded to the brightly coloured Supergraphics aesthetic of the early Seventies at a time when fashion was only beginning to reassess ‘second hand’ as ‘vintage’. But Diesel’s relevance extended beyond the jeans and the clothes, beyond its accessories and underwear and trainers and fragrances to a broader branded culture. Its flagship stores felt like nightclubs, with DJs on turntables and decent sound systems pulling in crowds on a Saturday afternoon. It started selling through its website years before most of us had internet access. And its advertising campaigns, shot by fashion photographers like David Lachapelle and Ellen von Unwerth, gave it an edgy reputation for controversy with images tackling issues of race, religion, sexuality and social justice, often in a way that was ironic or in questionable taste: a US World War II victory parade restaged to show two sailors kissing; a black swimmer diving into a whites-only pool in apartheid-era South Africa; a poster apparently encouraging parents to teach their children how to shoot a gun.

Martens remembers this era well. ‘Yeah, I’m nostalgic about it,’ he admits. ‘We lived through the Nineties wearing Diesel. It’s the first brand I was aware of buying. I remember washing dishes at 15, 16, illegally in the restaurants in Belgium to earn pocket money to buy jeans. “I want THAT brand, I want THAT denim” – the blue denim with the brown coating that would disappear little by little. Also, the grey knitwear with the blue stripe…’ He loses himself in his past for a moment. ‘Anyway, yes, Diesel was really my first conscious buy.’

Before that he’d shown little interest in fashion, but he did have an appreciation of historic clothing, largely influenced, he thinks, by his home town of Bruges. ‘It’s a cute little town in Belgium known for being very medieval, very Sleeping Beauty – the Venice of the North, they call it. So I grew up in this kind of fairytale where everything is very pretty and historic. So as a child I was very much into history, although I saw history as this kind of Walt Disney movie.’ A budding artist, he’d spend hours drawing historic figures he’d read about or seen on TV documentaries: ‘Cleopatra and Caesar, Napoleon or Marie-Antoinette. And the main focus was always their garments. A lot of detail would go into what they would be wearing.’ At the time, he comments, he didn’t think of this as having anything to do with fashion.

At university he studied interior design. A field trip took him to see the celebrated Belgian architect Marie-José Van Hee’s renovation of the Fashion Academy building in Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts. ‘That’s when I discovered that there was actually a fashion academy in Belgium,’ he says wryly, ‘which was apparently famous.’ After graduating, he was at a loss as to what to do with his life. ‘I was way too young and not at all responsible enough to do work. And then I remembered that beautiful building. I was like, I would be really happy to go to school in such a nice environment. And fashion could be funny; why not?’

Unsure as to what a fashion degree might entail (‘Do you have to sew or not? I didn’t even think about it’), he sat the entrance exam. ‘Strangely I got accepted, for some reason.’ He fell in love with fashion, he says, almost immediately, ‘on day two or day three. Suddenly there was a world opening up to me in the Antwerp Academy, where everyone is from all over the world, and it’s all very artistic and experimental and explosive. And me being this Belgian kind of normcore guy, I was like, “This is, WOW, amazing!”’ He wasn’t a very promising fashion student, though. ‘Like, I’d manage to pass, but on the second attempt.’ It all came good in the end – ‘something went click! in the third year’ – and he graduated top of his class.

For Martens, reconnecting Diesel with his teenage memories of its heyday isn’t an exercise in nostalgia. He sees it as his job to ground his work in the archive, noting that after 40 years it’s natural for a brand to become so overfamiliar with its own past that it starts to overlook its value. ‘It takes someone from outside to go, hey guys, actually what you’re sitting on here is worth a lot of money and is actually really beautiful.’ Even more importantly, much of the archive feels contemporary to him right now. ‘I see it more and more in Paris when I’m taking the Metro: the kids of today are wearing the exact same clothes we used to wear when I was a kid. It really is a revival of the late Nineties and 2000s. So the Diesel archive fits perfectly in there. I can get things out of the archive that are identical to what you want to wear today.’

The archive is housed in a cultural museum in Breganze. ‘It’s so sexy. Three floors of everything. It’s huge! They’ve managed to keep 90 per cent of what they’ve produced there.’ While his work designing collections for Diesel extends beyond simply reviving old pieces – ‘I have a creative ego, so I could not only do makeovers of the past, you know?’ – he says there is an element of his first collection that is ‘definitely reinterpreting the history, reconnecting to the founding DNA of the brand, which is the whole MTV pop culture, the whole distressed denim culture – that’s very hot, it’s what the world wants today. And then of course, yes, adapting it and also introducing new ideas and new identities and new personalities. It’s all about finding that balance. That’s what everybody’s doing, no? That’s what Pieter [Mulier] is doing at Alaïa, that’s what the guys are doing at Courrèges. Sometimes it’s not bad to reconnect with your fundamentals, no?’

Beyond the seasonal collection, Martens has also introduced a new line, Diesel Library. ‘It’s a collection of essential denim pieces – really iconic, not too fashion-y because it’s a carry-over collection. It’s going to be fundamental to our brand as it’s supposed to be 40 per cent of our turnover.’ For the Library, he has completely overhauled Diesel’s production chain. From the pesticides used on cotton fields to the dyes to the vast volumes of water it entails, the industry-standard production of denim is notoriously polluting and wasteful. In 2022, Martens notes, the least you can do is make sure you produce clothes responsibly. ‘For the Library, it needs to be the cleanest denim we can find today at that level of mass-production.’ It comes at a cost: ‘The denim is now 20 per cent more expensive,’ he points out, while some of the classic Diesel fabric blends, washes and treatments are no longer available, ‘because as of today a sustainable equivalent does not exist’, although he is confident that he can create alternatives.

‘Social and environmental accountability are in the DNA of the brand,’ he continues. ‘We were talking about social issues and taboos in the big advertising campaigns of the Nineties.’ In almost every interview since taking up his new post, Martens has highlighted the impact that David Lachapelle’s Diesel campaign image of the sailors had on his younger self, showing two men kissing at a time when such sights were not to be found in mainstream media. ‘That arrived in my daily life in Bruges, in my sheltered little city, so I think Diesel in the Nineties did play a role in opening people’s eyes.’ Today, he comments, that commitment to social progress has to extend to the issue of environmental sustainability, ‘which is just as urgent’. He is extremely proud of how responsive the company have been to his call to clean up its production, and how quickly they have achieved it. ‘In any other fashion group the discussion would probably have taken two years before they would have met the challenge. At Diesel it took me six months. Everybody went for it. It really is a miracle.’

Martens attributes this flexibility to the culture inculcated in the company by its founder, Renzo Rosso. ‘That’s the way he has always worked, being very caring and sticking to his guns. I think the whole company follows that mentality.’ The myth surrounding Rosso – the teenager who started out making jeans on his mother’s sewing machine, the industry maverick whose innovations in denim production made him the billionaire rock’n’roll entrepreneur who now owns Margiela, Marni and Jil Sander – still looms large over Diesel. If not actually present in the building, Rosso is still very much in the neighbourhood. ‘He’s living in Breganze and is there if I want him. So there’s dinners, breakfasts once in a while. He’s extremely welcoming and when I need him I can text him, when I have questions I can ask him things.’ Rosso’s decision to appoint Martens reflects well on the founder’s reputation for keeping his finger on the pulse culturally and never making do with playing it safe, I comment, and Martens seems to agree. ‘I think Renzo did a very good job in choosing me!’ he says, laughing.