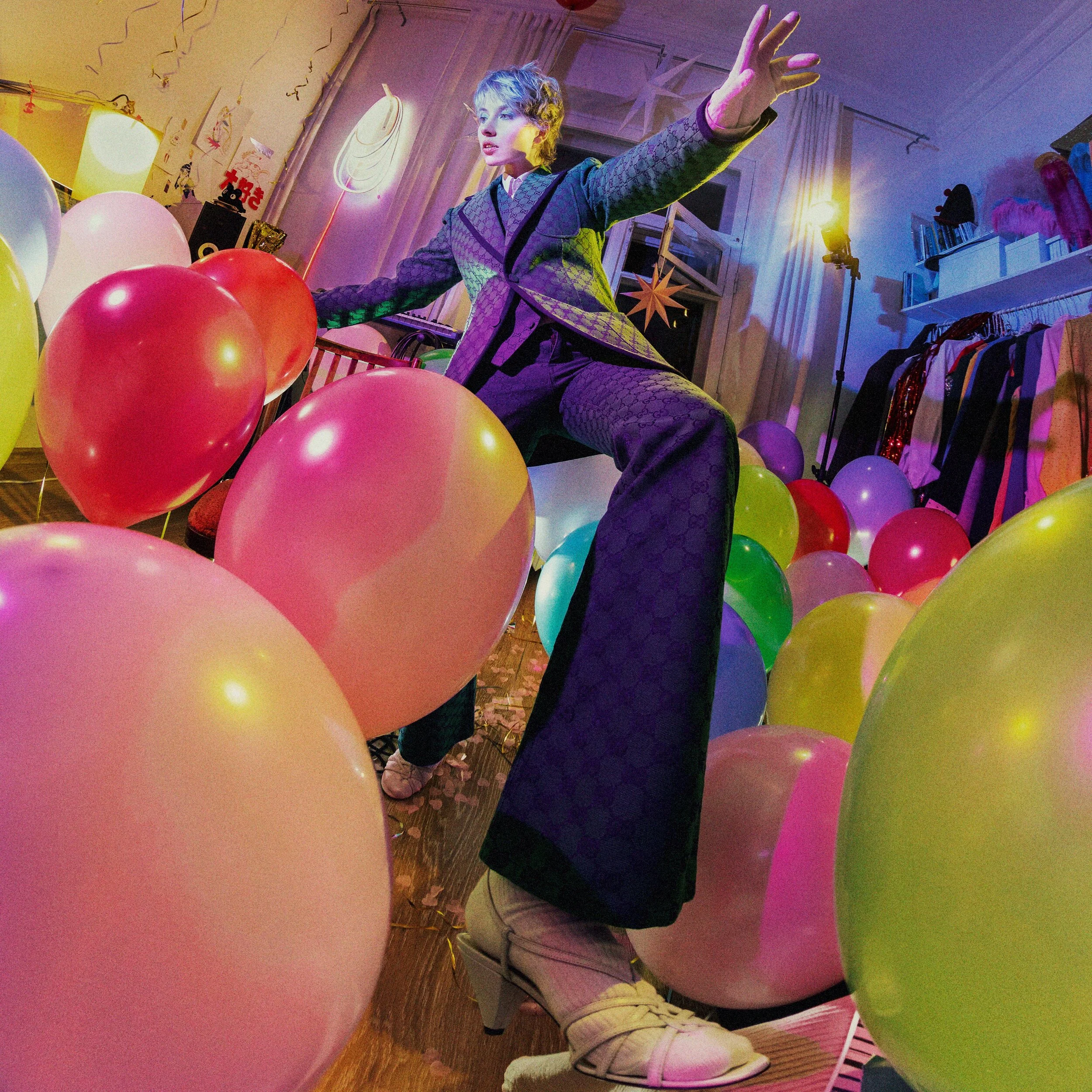

Gui Rosa.

Twenty-five-year-old fashion designer Gui Rosa is describing the conditions in which Till Death Do Us Ride – the film he made with his creative partner in crime Harry Freegard to showcase his capsule collection commissioned by Gucci – was shot last October. He took his clothes – frilly, flumped-up layers of crochet, skimpy distressed denim, knitted biker boots and very, very short shorts – his cast (‘all straight boys – none of them could act’) and a massive, ancient VHS camera and set up on a deserted bit of road near his home in Stratford, East London. But as soon as they began shooting the first scene – a model in multicoloured crochet driving up and down on a big motorbike – they were met with abuse from a bunch of bigots. ‘They were a few metres away, screaming at us. And then they called the police.’ A police van pulled up, and Gui was forced to explain what was going on. ‘But they thought we were filming some soft-core porn thing. Because it was all very naked, see-through jewelled things.’ Nevertheless, Gui and his crew were left to get on with it.

The hecklers meanwhile had disappeared. ‘So random. You don’t usually see anyone in this area – and then them.’ He pauses. ‘I don’t think I’d have it any other way! A bit of adrenaline. It was fun.’ Their reaction, Gui points out, was consistent with the energies that inspired these clothes and his MA graduate collection that preceded them: the antagonism between conservative expectations of cisheteronormative masculinity and extravagant breaches of its codes. An antagonism that Gui is all too familiar with, having made and worn such clothing on the streets for years, and having experienced the reactions it provokes from insecure men. ‘A lot of the MA collection was fuelled by me going around and being catcalled by men in vans. I was like, “Fuck you! What are YOU wearing?” The collection was a mash-up of that and myself. I think there’s something to be said about that subject position between my frivolous textiles and their strict sort of uniform.’

Men driving motor vehicles is a recurring point of reference in his work. The research for his MA collection consisted of hitchhiking around London while dressed in his usual day wear: ‘Top-to-toe sequins and accoutrements. I’d wear a mixture of fashion stuff like a Miu Miu coat with some sparkly stretchy sequinned dress from Oxfam with acid-printed Claire’s tights. I encountered lots of closeted guys.’ He gives a big laugh. ‘And really nice old gay guys. But I never encountered anyone I was afraid of, or where I thought my life was in danger.’ His original plan had been to hitch-hike across the United States in the style of John Waters’ travelogue, Carsick. ‘But my tutors were like, “No – you will DIE.”’

Gui unveiled that collection as part of Central Saint Martins MA show last February, in the fashion calendar’s last flurry of activity before the first lockdown. Then of course, 2020 went the way that it did, and everything stopped. Gui and Harry had secured space to mount an exhibition of work in Soho in May, but that was cancelled. Since then Gui has been working on special orders based on the looks from his show. ‘It’s basically me and a crochet hook, like all day long.’ It’s a skill he learnt from his grandmother as a child, back home in Lisbon, Portugal. ‘She is nuts!’ he laughs, although he clearly adores her. ‘She would make me crochet rows without end until it was perfect for her. She’s very traditional in her crochet.’ To this day she helps him crochet pieces, although the fact that his take on the craft is decidedly not traditional can set them at odds with each other. ‘We’re both Southern European gals, so it’s mostly shrieking and screaming – that’s how we communicate. I think that’s where I got my, er…’ He laughs. ‘I have got a vein of dramatics.’

Fortunately the slow and fiddly nature of crochet is something he enjoys massively. ‘I do love it, I find it really calming and soothing.’ Did he imagine this is how his life would be as a designer, sitting at home with his crochet hook? ‘Right now I think it’s the only way I can progress. I’m trying to figure out how viable a business that is! But for now I am surviving making these very time-consuming things, and luckily there are people who are willing to purchase that.’

Gucci’s invitation last autumn to be part of GucciFest – its film-based, multi-brand-collaboration alternative to the conventional show schedule, which had been left in tatters by the pandemic – was a welcome surprise. ‘They’re fantastic,’ says Gui, ‘so altruistic.’ Gucci’s commitment is ongoing: Gui is creating a further collection with them for spring, with pieces being produced for sale. Going forward, the challenge will be finding ways to create more commercial, less labour-intensive manifestations of his sensibility that don’t compromise his vision. But it’s tricky, he says. What’s special and unique about his work lies in the excess and intensity of the skills and the vision that produced it, and it’s hard to hold on to that while ‘making something that’s affordable’.

So Gui’s skill with a crochet hook will forever stand at the heart of his creative universe. ‘I’m going to carry on doing this regardless of whether there’s anyone who wants it. Hopefully I can do that. It’s just finding the… financial possibility, getting the kind of people behind you who can help you carry on doing fun things. Like, I’ve got such a huge admiration for Matty [Bovan] – he is just doing whatever he wants, which is fantastic. Because we thrive on that fantasy, we need it every Fashion Week. I don’t care if he’s going to do something that’s going to sell, I just want to be amazed. Hopefully there will always be those sort of people.’ Funnily enough, the restrictions of lockdown may well have sharpened mass appetites for the unrestrained imagination exemplified by the likes of Gui and Matty. ‘Spending on entertainment during lockdown has gone through the roof,’ Gui notes. ‘Everyone’s got this hunger for things that take their attention away from the mundane.’