Maria Grazia Chiuri.

‘Do I make myself clear?’ asks Maria Grazia Chiuri. ‘Yes, Maria Grazia, understood,’ quips her daughter Rachele Regini. There is moment when a parent stops teaching their child and learns to listen instead, as mother and daughter, now working side by side as creative director and cultural advisor at Dior, go head to head

Maria Grazia Chiuri is sitting at her desk in her design office at Dior and her 24-year-old daughter Rachele Regini is sitting on the floor in the library in another part of the building. Mother and daughter. The creative and the academic. Working together but within their own spheres. Rachele may have been ‘born’ into fashion while her mother was working full throttle at Fendi, but her time spent studying art history and gender studies in London at Goldsmiths unsurprisingly made her question the very world she was brought up in. Both Rachele and older brother Niccolò haven’t shied away from critiquing their mother’s supposedly vapid industry and its values.

Maria Grazia clapped back. You want to make change? Come here and see how you fare! Challenge duly accepted. While embarking on her PhD in gender studies, Rachele has therefore taken on the role of Cultural Advisor at Dior, to help Maria Grazia and her team better integrate cultural references – and ultimately values – into the collections and within the messaging of the house. It smacks of nepotism, and within 10 minutes of listening to the two converse you realise their relationship and its underlying tensions propels their creative endeavours towards a better place. They barb. They roll their eyes at one another. Maria Grazia speaks at length and Rachele is itching to interject. It’s the repartee of a mother and daughter who clearly over the years have come to serious blows with each other over the fashion industry but have also gained respect for each other’s perspective. In essence, Rachele helps Maria Grazia engage meaningfully with female artists and academicians in her collections – a dialogue that has become one of the core foundations of her tenure at the house – while Maria Grazia gives Rachele the opportunity to make incremental change within a very big system.

The starting point of their journey was THAT Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ T-shirt, where Maria Grazia put out an earnest statement for her debut collection at Dior and the fashion world frothed at the mouth. Can fashion promote feminism through a £700 T-shirt? But by placing that statement – and others, such as art historian Linda Nochlin’s ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ and Judy Chicago’s installation of feminist hypotheses – within a fashion context, Maria Grazia already achieves the very thing her critics claim is beyond her remit as a designer: to have a fashion house align itself with more than mere aesthetics and to enlighten a huge audience of the very existence of these feminist fore-figures. As one of those former critics Rachele was quick to point the finger, before entering into the inside track at Dior and realising that changing an entrenched system takes time and – a word that crops up in conversation, again and again – compromise.

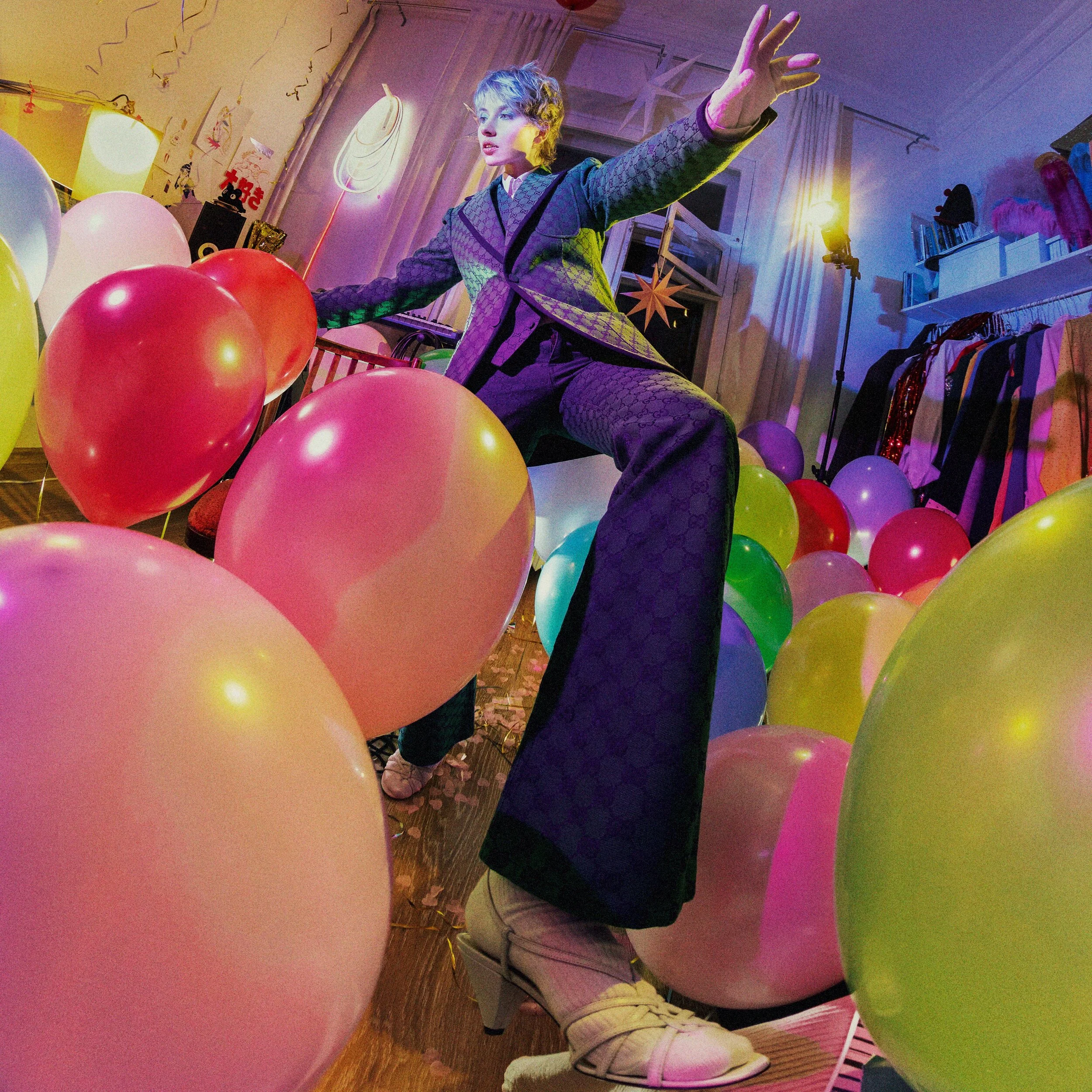

And realising that what we desire to wear can’t be weighed down with feminist theory and messaging all the time either. For pre-fall, what Maria Grazia desired more than anything was to DANCE. With somebody. Anybody. While many designers reacted to the pandemic with talk of ease and comfort (code for boring), she veered out of her comfort zone into hot pinks and bright yellows, loud leopard print and a pop art sensibility. She was thinking of Fiorucci, Warhol and what the K-pop band Blackpink would have worn if they had been styled by Maripol, the legendary photographer of the Eighties club scene in New York, who shot the collection’s look book. London-based photographer Jessica Madavo took that Polaroid cue and invited her friends to get intimate with the collection. ‘You’re going out for the first time after lockdown – here’s a rail, what are you going to wear?’ was Madavo’s vibe – and incidentally, Maria Grazia’s too. Originally from Johannesburg in South Africa, Madavo grew up in England and escaped into the photography darkroom as a way of avoiding fitting in at school. She broke through with a series entitled ‘Afro’, exploring black women’s relationship with their natural hair, and has also recently produced a zine of self-portraits shot during lockdown alone in her student flat. ‘I’m never just “done” with a project,’ she explains. ‘It’s a safe feeling for me to know that I can come back to something that is already established.’

In a year that seen most of us learn to live in isolation and retreat within, Maria Grazia has conversely found herself with stronger connections to her circle, be that friends, colleagues, people in the Dior ateliers and supply chain, or family. The impetus to create bound Maria Grazia and Rachele with a common purpose. And now 2021 beckons. What would be perfect for both of them? First a vaccine for all, and then preferably a huge party at the end of this tunnel. ‘Mi sono spiegato?’ is Maria Grazia’s most used phrase. Rachele says her mother quite often repeats herself, to ensure her point is heard properly and understood. We hear that loud and clear.

Maria Grazia Chiuri: When I had Rachele, I was working at Fendi. It was a very family-orientated place. It was very normal to have a designer who’s also a mother. Sometimes I would come into the office with both Niccolò and Rachele. They would help me set up the collection in the showroom. They are both born in fashion, in a way…

Rachele Reggini: I’ve seen pictures of me and Niccolò in the showroom. You tell stories about us sorting out bags before we could walk!

Maria Grazia: The reality is that with Rachele, her first meeting with fashion was when she was six months old and I was going to factories. In between meetings, I would breast-feed her. Then she would sleep. And then we’d continue the meeting talking about accessories.

Rachele: My first actual memory of being with you in a fashion environment was Mr Valentino’s last show in Paris and I was wearing a Bonpoint dress. I just remember feeling very confused because everyone was just running around.

Maria Grazia: Then you grew up. You became super radical. You criticised not just the fashion system but capitalism at large. They were born in another moment. What we did was try to understand them and see where they were coming from. Even now it’s never finished, the criticism.

Rachele: To be honest, you say criticism but I don’t think of it that way. We were growing up and going through these stages. You go from knowing what your parents tell you and what you’ve experienced.

Then when I was in London, studying feminism and art history at Goldsmiths, that opened up another dimension that made me question things. You had just started at Dior when I was at uni. Your incorporation of feminism inside the fashion system was problematic for me, because I was coming at it from an academic context. I was afraid of values of feminism being addressed within a system contributing to the oppression of women, which I had a problem with. I remember you would come up to me asking about artists to collaborate with and I would just be like, ‘No! You cannot do that!’

Maria Grazia: The honest truth is that it wasn’t a planned calculated thing but actually a necessity for me. After many years of working with another creative director – a man – starting this new chapter in my life alone was a moment of reflection about myself, about my creativity and what it means to really work in fashion. It was a delicate moment in my personal life. I was shackled to stereotypes in my mind too, and was torn. I’m a mother and am dedicated to my family. It was a sort of suffering. I had to decide for myself what I wanted to do. To stay in a design partnership, come home to my children and husband and have dinner with them? Or decide to be a woman alone, in another country and at this very famous house. Of course, my family support me entirely. But when I listened to Chimamanda talk, there was something in her argument that really touched me. She expressed what I wanted to say so well. Nobody at the house understood, really, and initially there was some difficulty as [Chimamanda] didn’t answer in the beginning. I wanted to write to her personally, so I actually had to get Rachele to help me.

Rachele: Do you remember after the show, she told us that she replied because the letter was handwritten? She said she hadn’t received a handwritten letter in so long and that it was worth replying just because it was handwritten. I explained why this feminist message was important to you as a person and as a designer for Dior. And that, honestly, it was coming from a very personal place.

Maria Grazia: The important thing for Chimamanda was that she had no interest in fashion. She was completely outside of it. She didn’t know what was Dior. I remember that she was super surprised that I was the first female creative director at Dior, because of the positions of female editors in magazines.

Rachele: It was interesting for me was that people had read into the T-shirt so much, when really it was done so unconsciously. It honestly wasn’t engineered. You listened to [Chimamanda’s] TED talk, bought the books and came back and wanted to work with her.

Maria Grazia: At the same time, I was conscious that we had touched a sticking point within the fashion system. Dior choosing a female designer was unexpected for the system at the time. The strong reaction was from within – less so from other fields.

Rachele: You also have to remember the timing. It was just before the #MeToo movement, so it felt extra pertinent.

Maria Grazia: The fashion world has never really reflected on their position. They didn’t have the distance from themselves to pointedly say that actually our world isn’t particularly feminist. I grew up thinking it was impossible to be a designer, let alone high up in a company or to be a creative director. The Fendi sisters were recognised as the owners but the creative genius was Karl Lagerfeld. But when I was working there, Paola and Anna did create. The stereotype in fashion or art is that the artist is male! When I made that statement, it was to send out a strong message about the state of fashion.

Rachele: I was coming from such an academic background that all I was doing was pointing fingers at the fashion industry. I remember you saying at one point, ‘Rachele, you need to actually start working and see what it’s REALLY like to try and incorporate your values into the fashion industry.’ It was a shock to realise how hard it is, even from the inside, to get these messages across. In academia we see things as black and white. In fashion you have to arrive at a middle ground, where you are still making desirable items while staying true to these feminist values that we put forward. You put me in a position where I could challenge myself, to grow up and realise that living in the real world means to come to a compromise and to arrive at change one step at a time and not all at once.

My role as cultural advisor is to continue to try and answer these questions that I had before, and continuing my studies on all of these themes that we want to incorporate into the collection as references, and how to translate them in a material way while staying true to these feminist causes. On the one hand I’m working with the studio and on the other I’m in touch with all the female photographers we shoot with and the artists that we collaborate with. Often you come up with a theme or you’ve read something that you’re interested in, or you find out about an artist you like. And then we do all the supporting research and find a way to create a meaningful dialogue between fashion and feminism, and between Maria Grazia and the artist.

Maria Grazia: It’s very important for fashion to have a new generation with an academic profile. When you criticised me, I tried to explain that we don’t understand that argument because I never had that kind of education. I didn’t study abroad. I really believe that my generation need to keep talking to the younger one. They can help us to reflect. When they criticise capitalism within fashion, even if I partially agree, I always ask, ‘But what can we DO?’ I invite them to take steps to make changes. I want to find that compromise. But compromise doesn’t mean something bad. It means finding a balance between different points of view. I really appreciate your rebellious spirit. But at the same time we have to be realistic.

Rachele: You take my rebelliousness and put it into practice. You confronted me and said, ‘OK, so you want to criticise me! Now see if you can do better!’

Maria Grazia: Fashion is a field where we touch a lot of things. We are creative but we’re also a commercial industry. In the past that creativity could be entirely isolated, but that’s not realistic today. The impact of the industry DOES matter. Sometimes what the fashion media promotes is something unreal. But from my perspective, there is heart in this system. We have to be honest. Creativity needs to find balance in a system that is complex. We have to give opportunity to people to create. I see today, everyone is saying we must consume less and make less impact on the environment. But how do we impact less without stopping creativity? Humanity wants to create. And in the end we are speaking about humanity.

Rachele: You’ve gone off topic, Mum!

Maria Grazia: When I hear people talking today: ‘Oh, we have to consume less, we have to be more conscious…’ But nobody wants to dress themselves in a uniform! Because I desire! I desire to be different!

Rachele: But the question is, OK, you desire – but what is the cost of that desire to the earth?!

Maria Grazia: Yes, I reflect on that! But humanity wants to express themselves with a new look! I don’t want to just wear a uniform.

Rachele: But you do wear a uniform!

Maria Grazia: Because I have no time, and I’m too busy thinking about desire, so I dress all in black. The reality of our clothes is more complex.

Rachele: It IS more complex. Fashion before was a smaller reality and less global. For me, the more problematic question [is], can fashion be a vehicle for a more feminist form of activism? Can an industry that has contributed to the oppression of women transform itself and be an instrument of freedom – personal freedom?

Maria Grazia: It’s true that there aren’t many female CEOs in fashion. But this isn’t just in fashion, it’s in all industries. In Italy we’ve never had a female prime minister…

Rachele: But now we have a female American vice president…

Maria Grazia: Honestly, I would like it if we didn’t have to think about the gender of people but only their quality – their level, their knowledge. It’s about humanity and kindness. We have to think about a different way of doing things. Last year, we went through a very shocked paralysis. We didn’t understand what was happening. Afterwards, immediately my decision was always to try and do what was possible. It was important to support the supply chain. Behind Dior there are a lot of people. If I have to say one thing about 2020, it is that I found sisterhood and connections with people that were resilient and hopeful for the future. I was really in close contact with my team, colleagues from around the world, people in the supply chain. Our common goal was to create.

Rachele: Personally, I learned how to slow down. Not being able to plan has been a challenge and just living day by day. It was an introspective year.

Maria Grazia: Introspective, yes, but at the same time I shared my introspection with my community. We had distance, but I shared a lot with people that I trust. There was warmth for me despite not being able to kiss or have dinners with one another! I really thought about what was actually a necessity for us. When I started the pre-fall collection I was so depressed. All I wanted was to do was to DANCE! In the studio, we decided we wanted to REALLY dance together in a room, not in an exclusive club. No masks, a lot of sweat and really loud music. Our dream when this is all over is to do a party, but not a ‘cool’ party.

Rachele: Everyone in the studio was picking their outfit for their post-pandemic party.

Maria Grazia: These are colours that I would never choose in my life! [But] you need something that would give you good energy. I wanted mirrored dresses! Yellow? Pink? Sure! When the marketing team saw it, they were a bit shocked. It was my reaction to what was going on.

Rachele: Everyone who works in the studio is very different and have their own tastes. When you’re designing a collection you get a bit of everyone. This was about a team bringing their ideas.

Maria Grazia: My studio is very dynamic. We are building a brand together. I’m a creative director but what I want to do is to give a new vision for this brand to move it in the future. I want everyone to feel that we are doing it together. I’m not a narcissistic woman – really! I’m obsessed with the PROJECT, without me BEING the project. Dior is a huge platform, which is why I want to share female artists and photographers through this platform in an honest way. Like Maripol, who shot the look book for pre-fall. She did my first portrait when I first started at Dior. That’s not a collaboration, that’s a conversation with a friend. Or like Rachele – when I say you’re my muse, it’s different from when a man describes a woman as a muse, as opposed to a mother describing her daughter. Rachele and my son Niccolò are references for me. There is a moment you think you have to teach them, and then there is a moment you understand when you have to learn from them. That really is the worst moment – when you realise you have to listen!

Rachele: When I think of muse, I think of people like Lee Miller in the surrealist world. Yes, she was a muse, but she was also one of the greatest photographers ever. Muse is a much-disputed term. I don’t feel like I am one… In the end, it’s what Frida Kahlo says: ‘I am my own muse!’

Maria Grazia: (With a big roar of laughter) And with that she has the last word!