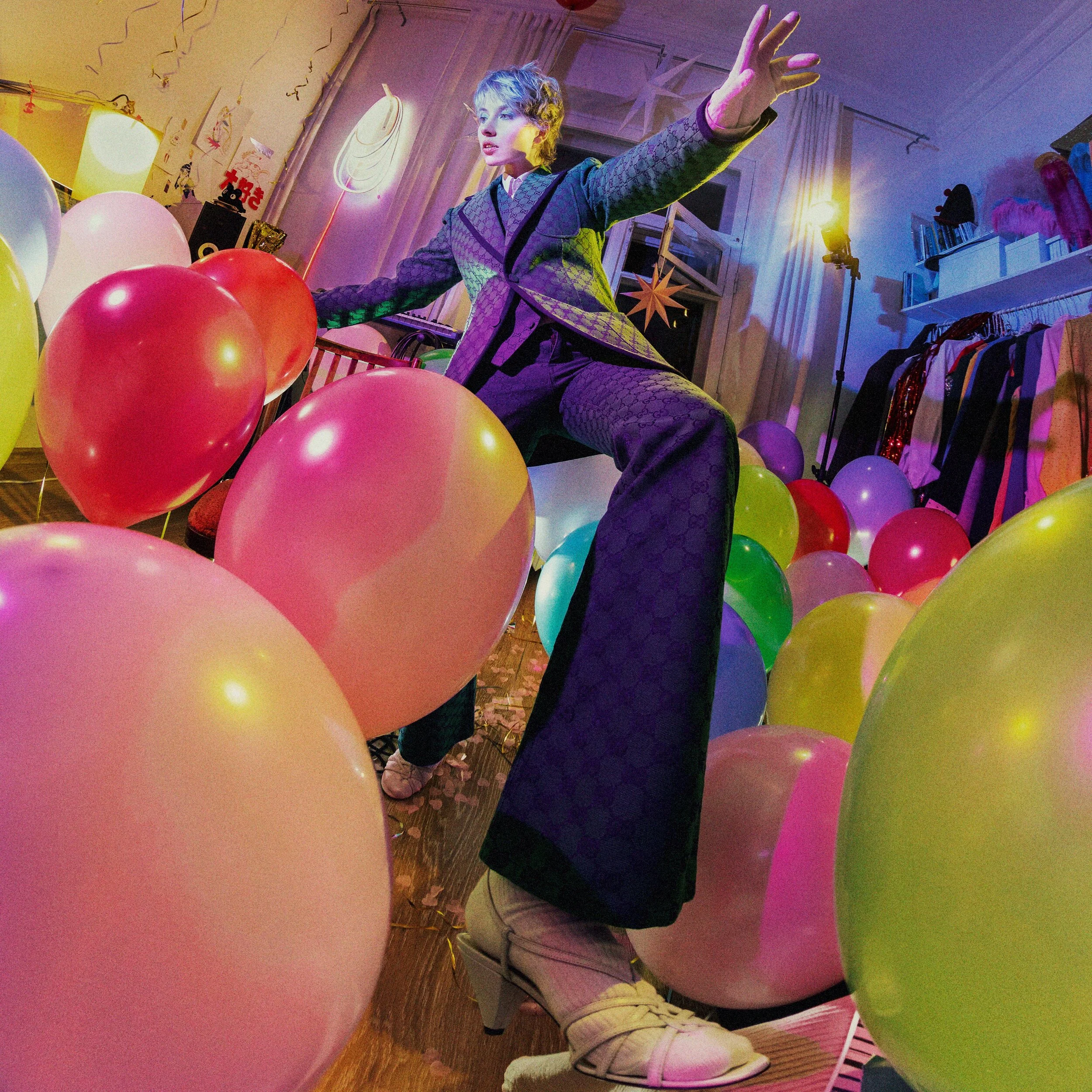

Michaela Stark in conversation with Enam Asiama.

Designer and image-maker Michaela Stark creates body-con couture for all bodies: clothes that bind, sculpt and reveal flesh in counter-normative ways.

It’s a rare sunny day in England and in typical 2021 fashion, we are experiencing technical difficulties on Zoom – the ‘we’ being artist and couturier Michaela Stark, plus-size advocate and self-proclaimed super-fat model Enam Asiama and myself. Michaela tells me that she has been admiring Enam’s work from afar for a long time. ‘I really respect her for the work that she is doing in normalising “plus-size” bodies,’ she says, ‘particularly bodies that she refers to as “super-fat”. I think it’s really important for this industry to be supporting voices of Black plus-size models and activists. I stanned at her “Open Letter to the Fashion Industry and Its Allies”,’ she says, referring to Enam’s article which appeared in the previous issue of Perfect. ‘I think she brought up so many amazing points in such an unapologetic way. A voice worthy of listening to!’

Twenty-seven-year-old Michaela Stark grew up in Brisbane, Australia in a house on a tiny no-through road in suburban West End. ‘It was a funny little road full of children all around the same age as me,’ she tells me. ‘I knew all of my neighbours to the point where I felt comfortable just freely walking into their houses as if it was my own. I felt no shame or boundaries in growing up on a street like that.’ But the idyllic tranquility of a small town soon grew tiresome. After studying fashion design at Queensland University of Technology, as well as a six-month stint at a Milan Design School, the entrepreneurial Aussie set her eyes on the grey-skied, smog-filled gritty city of London. She moved there after graduating in 2016, becoming an artist in residence at Alexander McQueen prestigious Sarabande Foundation in 2020.

As a child, Michaela was far from a wallflower. For those who knew her, the thought of her one day owning her own label, and taking such a hands-on approach to designing, would not have come as a shock. ‘I used to rally all the kids into going along with my elaborate plans to become rich. We did all the classics – lemonade stands, garage sales etc – with not much financial success. I remember once I decided to put on a play when I was about five years old. I wrote the script, did the costumes and cast all the children in the neighbourhood – giving myself the star role, as well as being the director! I invited absolutely everybody I crossed on the road, whether or not I knew who they were, promising them snacks and a great show for as little as two dollars entry. And they all showed up in support! Everyone! Even my next-door neighbour, a man who had legally changed his last name to Freemarijuana and ran for [Queensland] senate as part of the HEMP party. He was the hardest catch for me because of his usual lack of enthusiasm for my rather… bubbly personality,’ she laughs. ‘So in my eyes, it was a success!’

And it has been nothing but success for Michaela Stark ever since who, after catching the attention of Beyoncé and being invited to work as a tailor to the star, was then commissioned to create custom pieces for the singer’s ‘Apeshit’ music video and later designed a look for Black Is King.

When asked how she would describe her work, Michaela explains that her process has enabled her to develop a great deal of her own sexuality, as in the beginning she would only design for and post images of herself. ‘A lot of it is modelling naked in front of a camera projecting the sort of fantasy that I like to see in myself and showing a lot of my naked body and naked skin. I think that’s a really big component of my work, showing parts of your body that society has conditioned you to hide. Because I think that sexuality, and sexuality coming from the female perspective, is something that we have been conditioned to hide, and that’s where the fantasy element comes into my work.’

Enam Asiama: What fantasy have you created around your body?

Michaela Stark: There’s a lot of amazing body-positivity imagery out there showing really beautiful, natural portrayals of a lot of different sizes of body, a lot of different representations, which I think is great. I think that because my work is [also] body positivity, it often gets put into that category. But the way I see it, my work actually doesn’t necessarily show the natural body: I morph it, I distort it, I emphasise some parts and compress others. I change it until it’s almost something different, but still celebratory of the natural body, still really heavily inspired by the body – it still draws on nature so much, basically. But because it’s not completely natural it almost goes into a fantasy element, because it’s this idea that you’re no longer yourself and that’s where the confidence comes in. Now that I’ve started working with the models, I realise that it’s almost easier for some people, some models, to show their naked body in my clothes than it would be for them to just get naked in front of the camera. Because once you start twisting and morphing and doing these crazy things, it gives you more confidence and you’re no longer necessarily vulnerable; it’s like your own body intentionally looks the way it looks.

Enam: I completely get what you’re saying. When I started modelling, I didn’t think about it in that way. But it was when I could see the vision of another designer – like you were saying about having this interactive process with people – that I appreciated moments like that, because it did allow me to appreciate the designer’s idea and vision. It made me want to execute it in that way, helping enhance that fantasy and elevate that work. I’m interested to hear what progression you think can be made in the fashion industry when it comes to the way different bodies are treated.

Michaela: The way I design is always so related to the body of the model: my clothes are all about enhancing the specific body of that model. So what I always do – and this is a hard ‘always’ now – is before a shoot I’ll meet with the model and have at least one fitting, if not two or three. The first one is usually just a conversation – like, ‘This is my work, this is what it means to wear my work.’ Then we start talking about their bodies and their relationships with their bodies, like, ‘What do you feel insecure about?’ but also ‘What do you love about your body and what makes you feel super confident?’

Enam: So it’s quite an interactive process, then?

Michaela: Yeah, absolutely, I try to make it as interactive as possible. And then after that meeting where I take the measurements and have that conversation, I’ll get them back for a fitting the day before the shoot, and that’s when I try all the looks on them. That’s also when I make sure they’re feeling confident, that they’re feeling happy, and of course tailor the looks properly to their body and make sure that it’s fitting them perfectly. Talking through the shoot, talking through poses, showing them in the mirror – it’s very much a collaborative process. For me, the main reason I started doing this is because when you’re a model and you show up on set, there’s a team of however many people on that set who’ve approved all the looks already, and for some reason you’re the one who doesn’t know what’s going, even though it’s your face in the picture. It can be really stressful to say no in that situation, and a lot of the time models will just say yes just because the pressure is on them. And then they’ll go home that night and be like, ‘What the hell did I do?’ They have no rights over the images at all. Once they’ve been taken, that’s it – it’s gone, [the owner] can sell that image and do whatever they want. So I really try to make sure the model knows what they’re getting themselves into and has an ample chance to say no, for us to have a conversation about it. It’s about making sure the whole time that they are completely on board with how their body’s going to be represented.

Enam: Now I want to do something quick that’s fun and a bit more lighthearted. Kitten heels or stilettos?

Michaela: Kitten heels – I can’t walk in stilettos.

Enam: Duvet or blanket?

Michaela: Duvet.

Enam: Pillow or no pillow?

Michaela: Pillow! Who says no pillow?!

Enam: What was the last song you heard?

Michaela: Probably something by Beyoncé. It always circles back to Beyoncé. Let’s say ‘Déjà Vu’.

Enam: Speaking of Beyoncé, what was it like to have someone approach you to work with and design for her? What was your first reaction?

Michaela: It didn’t happen quite like that, but my first reaction was, oh my God, I’m going to scream. Genuinely I was like, ahhhh!! I was a biiiig fan of hers. I died. But actually I was approached initially to become a tailor for her, like a seamstress on set, and then over time I worked with her and her stylist Zerena [Akers]. [But] even just that, I freeeeaked out. I was on the phone with my friend just screaming. I didn’t really believe it was real, it was all so quick. It was a phone call and then an ‘OK, you need to be in Paris, like, now’, and then all of a sudden everything was happening. But yeah, initially I screamed. And then every time something got released that I was involved in, I screamed again!

Enam: I can only imagine! So as soon as you heard that, did you automatically know what you wanted to design?

Michaela: With the work that I was doing for Beyoncé, I worked closely with her stylist who was also in communication with the creative director, so it was very much a team effort. Obviously since I’ve been working for Beyoncé – it’s been a couple of years now and I really take the process a lot slower – I’ve learned to be super, super personal with the person I’m designing for.

Enam: Do you find that the reception your work gets is because to some people your body may be seen as a lot more palatable or desirable?

Michaela: Absolutely. I can see that my body is definitely more palatable, especially at the moment because I’m not – the phrase you used – a ‘super-fat’ model. I use ‘plus size’ as a loose term because I would be considered plus-size in the fashion industry, but not necessarily in mainstream culture. So I can see why that makes my body more palatable. Saying that, though, I think my work morphs my body so much that by the end of it, it’s not my body… It’s my body accentuated, basically.

Enam: I wanted to ask that question just because what you do is so unique, and a lot of conversations that we have in the fat-acceptance movement are about this idea that people don’t understand how much harder it is that you can’t pick a day where you want to not be fat and a day where you want to be smaller. I think you often see fat bodies because it’s becoming a lot more mainstream, and body-positivity specifically has become more mainstream; that taps into more the positivity side of things where all bodies should be celebrated, without actually addressing the fat-acceptance aspect of things. And I think with you there’s hope there, because you understand some of the actual challenges that go beyond just the physical body – that it’s actually a mental thing too, talking about how much the female body in general is policed and how much pressure is put on us.