Perfect˙

Magazine

Issue Two.

(Acts Of) Fashion.

Writer: Bridget Foley.

In the wake of the pandemic, what purpose should fashion now serve? Is fantasy irresponsible? Does couture have any relevance? And is there any point to the runway show? Bridget Foley considers the possibilities, consulting some of the industry’s most thoughtful designers

Valentino’s Pierpaolo Piccioli typically creates an elaborate mood board for every collection, a mix of old and new. It might include images of artwork, architecture, elegant women, flowers, texts, from which he extracts something – a colour, a line, extravagant decoration – to somehow incorporate into a single coherent runway statement.

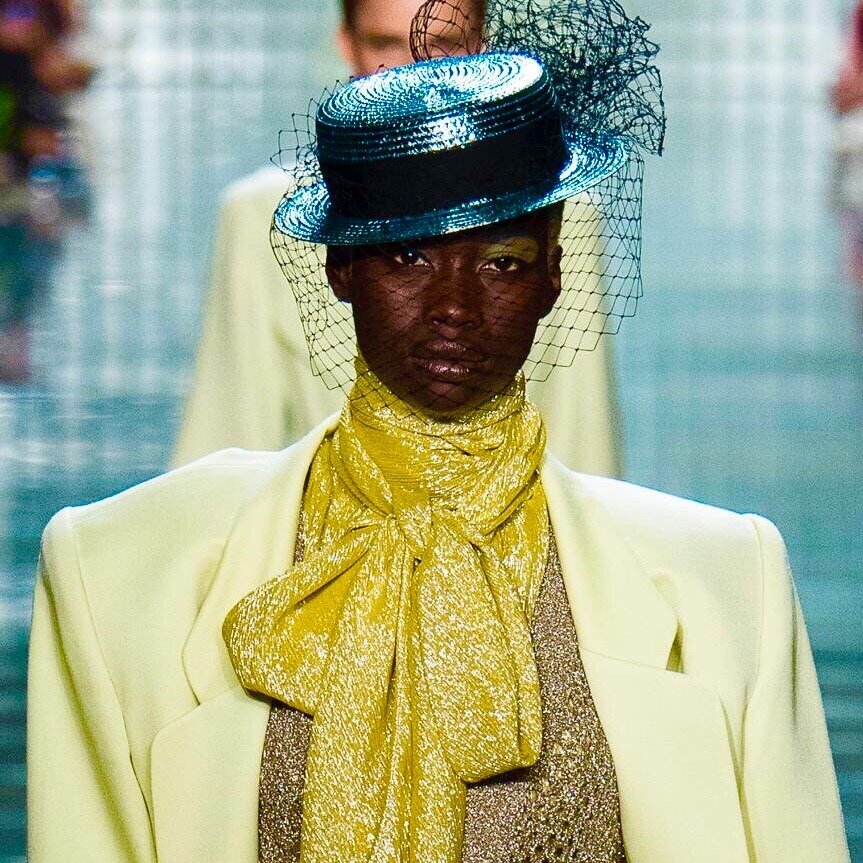

For his most recent collection, the exquisite spring 2021 haute couture he presented online in January, Piccioli did such a mood board, covered with visuals from Burri, Fontana, Giacometti, Brancusi and, something of an outlier, Leigh Bowery, in full, glittered make-up regalia. The artists were there because Piccioli took inspiration from their processes, eschewing applied decoration while making a collection pure in form, even minimal, its base materials speaking for themselves. (Conversely, Piccioli invoked Bowery ‘to break the rhythm of minimalism’.)

“I wanted the narrative to be the collection itself,’ Piccioli said. ‘I wanted to get to the spirit of couture, the idea that it was clothes. The point of view was clothes. I wanted to do an act of fashion for this collection, an act of creation.”

PIERPAOLO PICCIOLI

The point of view was clothes. An act of fashion. To some, that language might sound ridiculous, insulting, even, to cast the creation of fashion akin to other ‘acts of’ – valour, courage, conscience. But those who believe that fashion runs more than fabric deep, that it can stir emotion and touch the soul, would argue differently. Over many years of covering this world, ‘an act of fashion’ is perhaps the most beautiful, concise statement I’ve heard articulated about the power of clothes. In purest form, the designer’s job and calling are to engage in acts of fashion while creating clothes that express something, often (but not always) beauty, and elicit emotion.

Not all that long ago, the primary focus of the apparel industry was to make clothes. The most exquisite or new or interesting or provocative or beautifully crafted or special in some other way among those clothes were hallowed as ‘fashion’. Fashion’s most recent golden age – a period of extraordinary creation, and in some cases, wanton excess – ran for about 20 years, from the early Nineties roughly through the Aughts – up to the fateful moment when the financial crisis of 2008/09 and the digital revolution careened together, rocking the fashion industry and the world. Since then, for about the past decade, we have witnessed a de-emphasis of attention to the fashion of fashion – to clothes – as other matters have taken centre stage.

Today, fashion has numerous far-reaching concerns, not least of which for many participant brands is navigating the Covid-19 pandemic deftly enough to merely survive. In addition, those individual brands and the industry in full must grapple with major moral and ethical topics – diversity and inclusion; environmental responsibility; ethical treatment of labour across the supply chain – all essential issues, long woefully neglected, that demand and deserve attention. Now, much of the conversation emanating from brands focuses on their corporate citizenship efforts. At the same time, the space between fashion’s haves and have-nots has widened exponentially, as the major brands and groups call the shots. Despite the fact that they produce some fabulous fashion, too often, marketing tail wags fashion dog, and that tail tends to emphasise brand power at the expense of genuine creativity. Along the way, while the clothes aren’t ignored exactly, they’re often far from the centre of attention.

Yet here was Piccioli, a brilliant leader of the couture genre, stating that his goal was to produce an act of fashion – to highlight the clothes. Simple and profound. ‘I feel that my language is fashion, and through fashion I can deliver my point of view,’ he said. He referred in part to belief in the currency of couture and his desire to debunk the mindset that it’s old and musty. To that end, Piccioli chose to highlight day clothes, keeping them apparently simple, despite unseen, remarkable complications of construction. And he opted to film a traditional show (sans audience) rather than commission a narrative piece. ‘When you see this kind of effortless human beauty on the runway, you can dream about the world with no boundaries of genders and of cultures,’ he said. ‘You don’t [have to] define it.’

That said, in order to convey the essence of couture, Piccioli conceived a collection that would highlight ‘the abilities of our seamstresses and tailors through dresses that could look minimal at a first glance. Truth is that nothing was really what it looked like; crochet wasn’t crochet at all but a silk handwork; the golden fur was a beige cashmere double coat with gold Lurex fringes.’ It all played as a major act of fashion.

So what elevates a single piece of clothing or full collection to that level? And is such meaningful today? As with any non-quantifiable entity, it’s difficult to articulate, yet coopting the US Supreme Court’s legendary ruling on pornography seems to fit: you know it when you see it.

And when you see it, is it relevant? Or has the culture moved on from consideration of sartorial creativity for its own sake? In a world struggling through Covid, and an industry striving to adapt while on the defensive about having ignored and contributed to major societal ills for so long, should designers still care if the viewer’s jaw drops and heart races at the sight of a perfect dress?

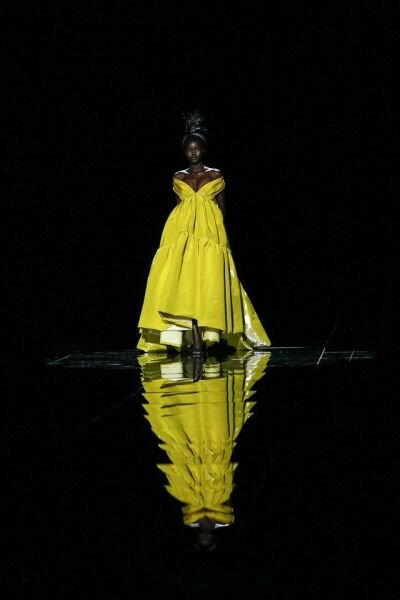

‘This is the never-ending conversation in my head, the question that doesn’t get answered,’ said Marc Jacobs. ‘The question which is, what is the purpose of it?’ Jacobs looks at the issue from a bifurcated perspective. Personally, he believes deeply in the sanctity of the fashion show, and has always designed his collections towards that very specific goal. While he has yet to produce a signature collection during the pandemic, he is now mulling doing a small group of looks, and knows it will require a shift in mindset.

“I understood when people came together and watched models on a runway, expressing a story, a designer’s fantasy set to music. I got it. That was my end goal, that’s what I worked towards. But that’s not what we’re working towards any more. And it makes you question, well then, what is it for? Is it supposed to solve a problem? Is it supposed to be a fantasy?”

MARC JACOBS

I always come back to the same thing: the purpose is to entertain and to inspire.’

Beyond the personal existential journey away from the runway that Jacobs must negotiate for himself, he is acutely aware of the fashion industry’s deemphasis of clothes in favour of more seismic issues. It both concerns and confounds him.

‘Everything needs to have a purpose that is related to a larger issue,’ he said. ‘What has happened is that there is now a polar binary kind of thinking – you’re frivolous or you’re responsible. I don’t know when or why this has become such a binary thing. With every other issue, everybody talks about how wonderful it would be if collectively we thought in nonbinary fashion and stopped labelling things – black or white; male or female. So I don’t understand why, when we get to talking about fashion, that you’re either contributing to [addressing] the problem or you’re escaping the problem. Can’t I contribute and have an escapist moment? Can’t I enjoy beauty and want beauty and still care about the environment and other political issues? I can do both.’

Jacobs is one of several designers queried on the topic. All are creators whose clothes reflect the artful consideration of their designers. Sacai’s Chitose Abe views acts of fashion in a problem-solving context. ‘My intention was always about creating clothes that made the wearer happy and confident,’ she said of her intricate, deftly built de- and re-constructions of fashion classics. ‘I think that fashion will always be relevant. Whether one chooses to wear T-shirts and sweatpants or a dress, one still makes a choice, and we are here to help make those choices.’

Yoon Ahn, co-founder and designer of Ambush and director of men’s jewellery at Dior, carefully mulled what constitutes an act of fashion. Her take: ‘The word “act” – it’s not only a noun. It’s a verb. It’s a living word. [As designers] we’re all participating in it. We are acting fashion, by putting our creativity out there.’

A self-described pragmatist, Ahn places a high premium on comfort but she doesn’t ‘like to take the fun out’. Nor does she default to the mundane, instead achieving the ease she loves with innovation, whether rethinking the classic T-shirt with a folding technique or, for fall, tossing a big, loose sweater over a green sequinned gown with attached helmet for a look of Space Age glam. ‘More than than ever this is the right time to give people dreams and joy,’ Ahn said. ‘I don’t want to give a cynical message.’

Across fashion, this seems to be a leitmotif – this isn’t the moment for dour or angst-riddled fashion messaging, not when everyone needs moodelevators (not to mention, a sound reason to buy clothes). Yet the creative perspectives remain vast and individual. Simone Rocha’s runway collections exude romance and lyric femininity, which she simplifies beautifully in those pieces intended for everyday reality. ‘The “act” feels almost like performance to me,’ Rocha said, ‘that moment when fashion can make you feel something, stir up an emotion from deep within or take you by surprise by invoking feelings… For me, yes [acts of fashion still matter]. It’s all about emotion, or else it’' just clothes.’

It’s never just clothes for Maria Grazia Chiuri. Since taking over as creative director at Dior, she has used her position and her runway in support of feminist issues, often in very direct manifestations. Still, Chiuri believes that currently, an element of fantasy is as important as concrete political statements. She presented her expressive spring 2021 couture in Le Château du Tarot, a compelling film by Matteo Garrone in which she chose to highlight the collection’s more opulent side. ‘Now is a new chapter,’ Chiuri said after the film posted online. ‘We don’t know anything about the future. We need a bit of magic to think positively… We are lucky that we can dream with fashion.’

Ultimately, though, Chiuri remains a realist. She pointed out that at powerhouse Dior, couture is far more than a tony marketing tool. The clothes matter a great deal, because they sell – a not insignificant matter as the pandemic rolls on. Dior has retained a significant client roster, particularly in Asia, where lockdowns have eased. If those clients weren’t moved enough by Chiuri’s haute acts of fashion to keep shopping, the results would reverberate well beyond Dior. ‘It’s not only [about] our atelier,’ Chiuri said. ‘It is also the couture embroidery house, the textile producer… If [Dior] has a problem, it’s a disaster for all of the supply chain.’

At the opposite end of the power scale from Dior stands Kevin Germanier, one of fashion’s young ascendants. He at first approached the idea of ‘acts of fashion’ from a research standpoint, googling definitions of ‘act’ (‘the action of doing something’) and fashion (‘clothes reflecting a time or a social event or a political something’). Then he decided to go with his gut reaction. ‘The way I work is quite spontaneous,’ he said, ‘so let’s not try to be smart. Let’s just be genuine.’ (Well, Kevin, genuine and smart.)

‘I believe as a designer, you are always making an act of fashion,’ Germanier said, while managing to identify something positive out of the pandemic nightmare: a newfound appreciation for something many of us once took for granted – getting dressed, and the inherent choices, ceremony and pleasures involved therein.

“We miss expressing ourselves. Every day you went to work, and you chose to wear what you wanted. Now that we are locked down, people are realising what fashion means.”

KEVIN GERMANIER

For Germanier, fashion means starting from a baseline of environmental responsibility without tempering the design quotient. His last collection, ultra-glam and razzle-dazzle, was designed with zero waste using upcycled fabrics. He acknowledges a front-end creative compromise to that approach, given the limitations of available materials. ‘But for me, limitations make me more creative,’ he said. ‘It’s more challenging. So yes, I am compromising, but not in a bad way. In the best way possible.’ Perhaps more established brands could take a lesson from Germanier. Yet the balance he speaks of may prove increasingly difficult to achieve if overall, creativity continues to recede as a primary point of focus. One doesn’t have to ponder too intensely to see the irony of diminished attention to acts of fashion – actual clothes – within the fashion industry. The creativity, the beauty, the provocation, the wonder are what drew most of its denizens here in the first place. Some still feel the rush. ‘When I look at a gorgeous Valentino show, my first reaction isn’t “was it [made] responsibly,”’ said Jacobs. ‘It’s, “Oh my God, those colours and the craftsmanship and what a beautiful dream.” I’m a fashion person. I want to love it or admire it or be inspired by it. I can be aware of and contribute in my own way to the bigger issues beyond fashion while still loving fashion.’

From Perfect˙ Issue Zero.