Juergen Teller captures David Bailey’s spirit, seen through his iconic studio and decades worth of memorabilia.

Juergen Teller and Dovile Drizyte spend an afternoon with David Bailey, photographing the artist in his natural environment: the legendary North London studio where he has worked for over 35 years.

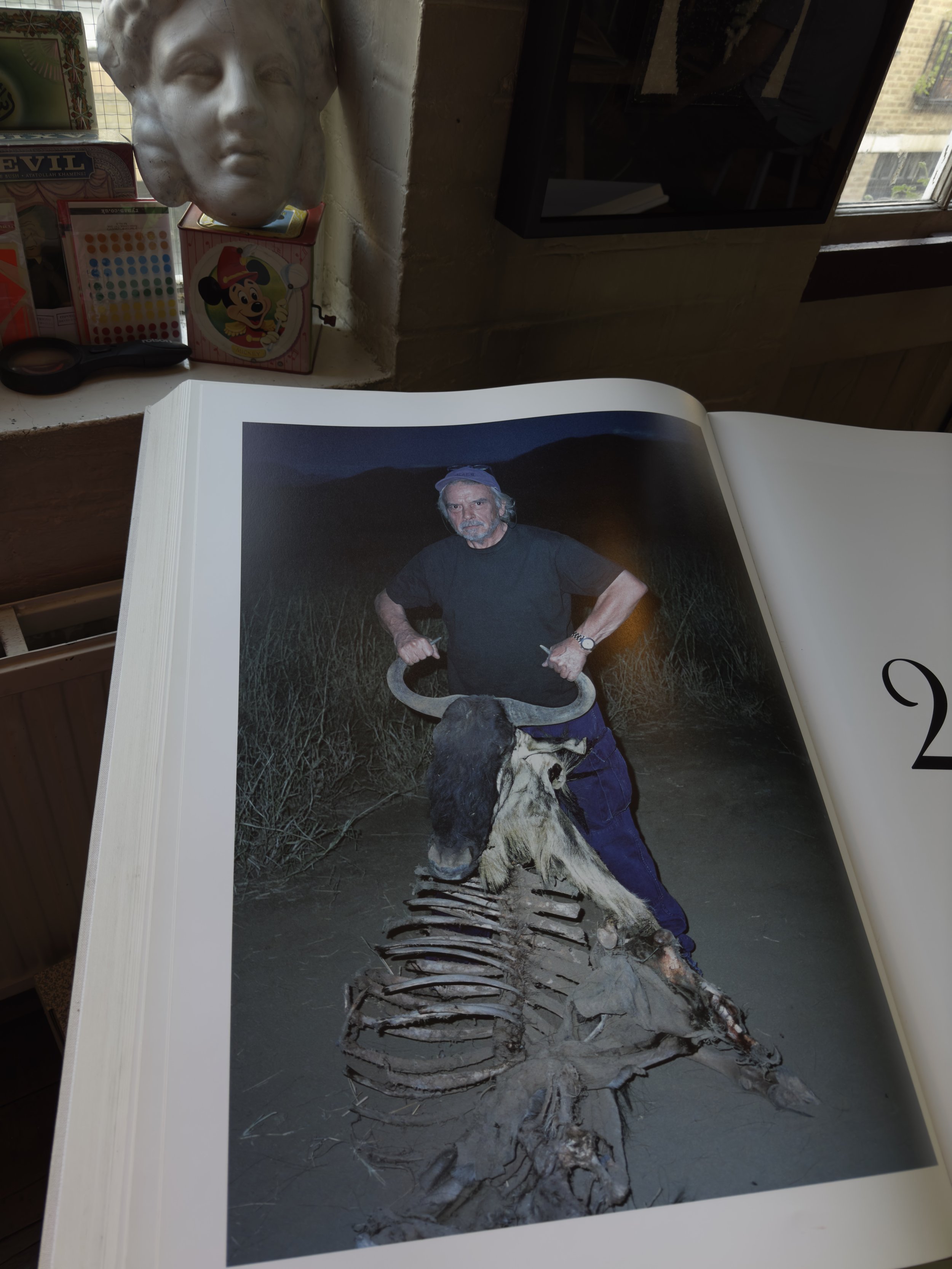

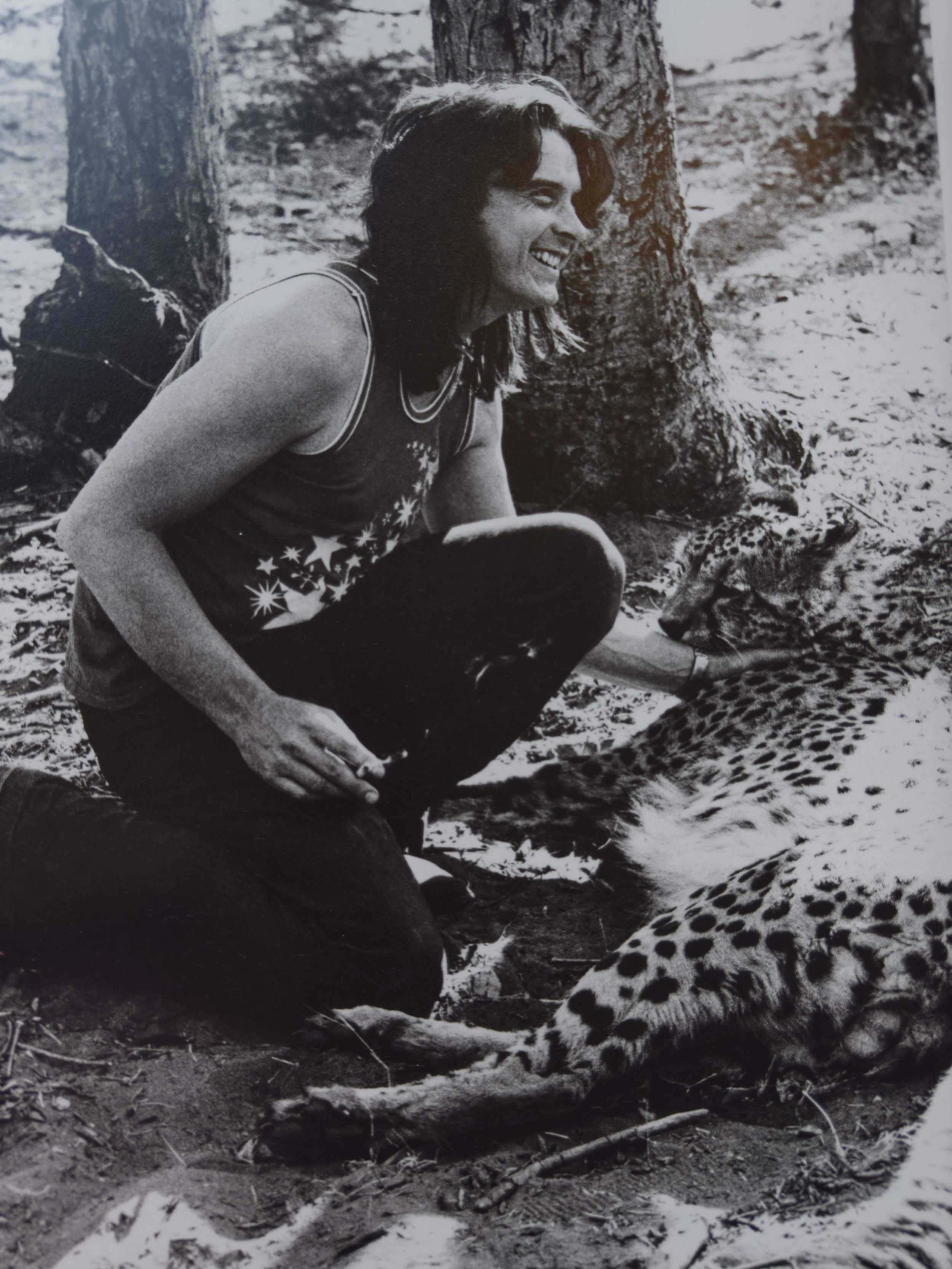

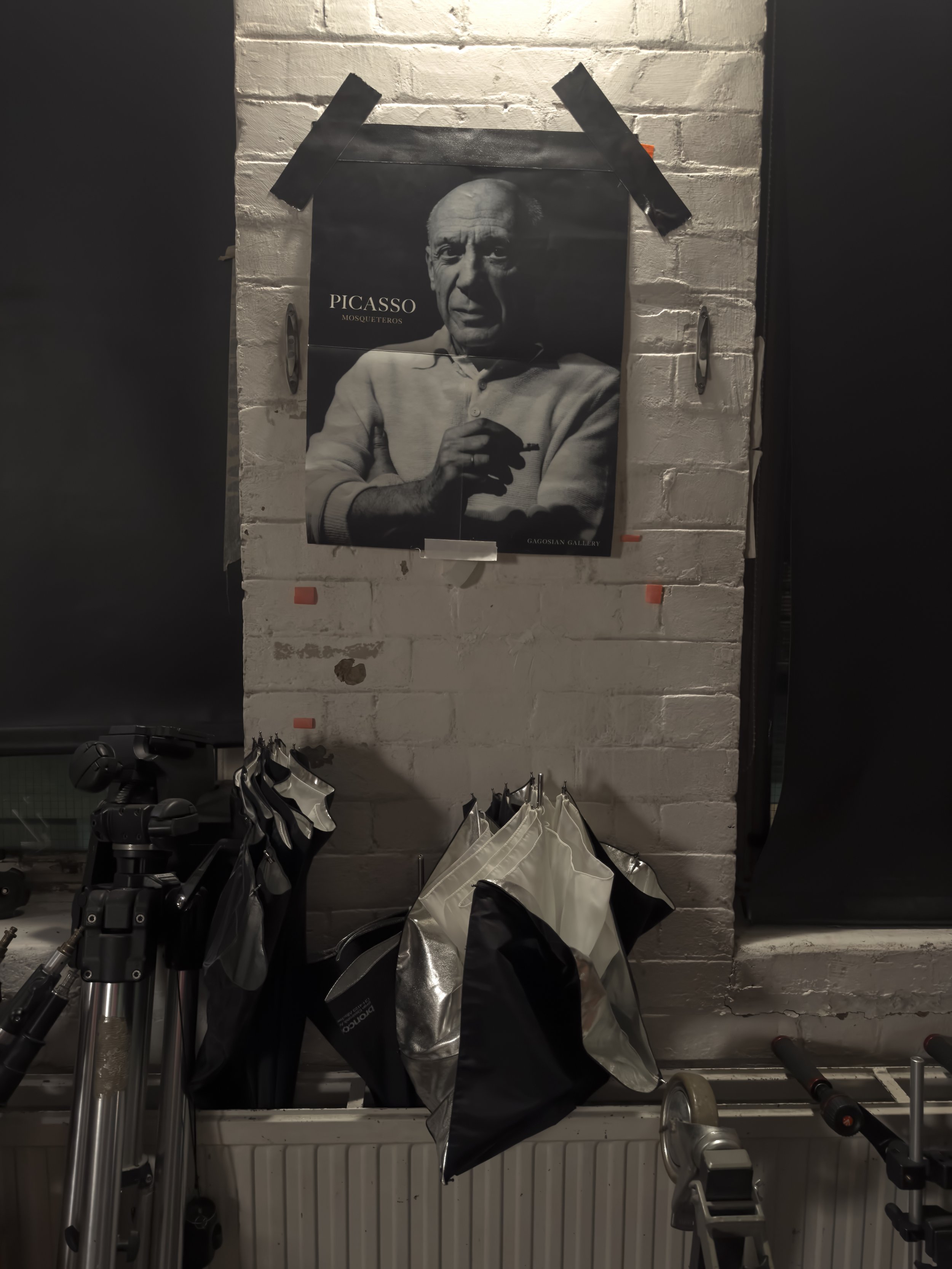

When Juergen Teller and Dovile Drizyte turned up at David Bailey's studio to be photographed, they had to wait a while before the veteran photographer got round to taking any pictures of them. 'For the first two and a half hours,' says Juergen, 'we just talked.' The three of them looked over images from Bailey's vast body of work, discussing who he'd photographed and how he'd shot them. In the Kings Cross loft where Bailey has been working since the Eighties, there were prints of Pablo Picasso and the Kray twins on the wall, and endless books and portfolios containing portraits of Salvador Dalí, Jean Shrimpton and Cecil Beaton, each frame prompting a comment or anecdote from the old master, as well as shots of the 85-year-old artist at work as a young man. Juergen and Dovile got to explore the more personal souvenirs too, poring over negatives and contact sheets, admiring Bailey's framed awards mounted over the toilet, tripping over the dusty bicycle parked in the darkroom.

Bailey had photographed Juergen twice before over the decades. 'He knows my work and he knows me,' observes Juergen. 'So there's a mutual respect.' They share a publisher in Steidl, 'so we talked about that,' and they even exchanged signed copies of their books. The couple presented Bailey with a copy of Auguri, which documents their marriage in 2021, while Bailey gave them a copy of his [title TBC]. The experience, Juergen says, 'was just excellent. I mean, we spent six hours with him.'

As the conversations continued, Juergen could sense that Bailey was waiting for the right time to start photographing, extending their stay with phrases like 'Oh, you don't have to go yet, do you?' and 'Would you like a drink?' 'He wants to loosen you up, you know?' says Juergen. 'He was so charming that you say yes and have a little whisky.' As a photographer, Juergen was all too aware of the little tricks necessary to create that perfect moment when a truly revealing image can finally be taken, waiting with the keen patience of an angler scanning the water for the slightest hint that something might be about to tug his line. 'I was aware that he was nervous, too. I could feel that he didn't want to take the picture, bang, right there. He wanted to learn about us first.' Juergen understood, because 'this is what I do also'.

Juergen was a familiar face for Bailey, but in Dovile he was presented with a new subject. 'I think he was very intrigued as to she was,' says Juergen.

'I was under the magnifying glass,' says Dovile. 'Juergen comes every time with a new woman, you know?' She laughs. 'But it was a huge privilege to be photographed by him,' she continues. 'I'm looking at these portraits – "Oh look, there's the Queen!" – and then it's our turn.'

Throughout the day, Juergen took his own photos of their time together, documenting the cluttered space with his iPhone. 'I fucking love that old studio,' he says. 'That's his home.'

Juergen Teller's own studio, where the couple are recalling that special day, couldn't be more different to Bailey's ramshackle loft. A contemporary purpose-built masterpiece over in West London, its pale concrete walls and slim architectural discretion saw it shortlisted for the prestigious Stirling Prize in 2017. We're in the main studio where two walls and the ceiling are dominated by glass, through which the watery light of a late afternoon in December is making little impact. The room is currently dominated by long trestle tables covered in print-outs of Juergen's work stretching back over 30 years. In two weeks, his exhibition i need to live opens at the Grand Palais in Paris, and they are making the final decisions as to which images will go where across its nine thousand square metres of floor space.

Unlike Bailey, Juergen prefers not to invite his subjects to his studio to photograph them. 'When I do portraits, I like to go to their environment,' he observes, although the likes of Jake Gyllenhaal and dancer Michael Clark have been shot within the studio's leafy little courtyards. The building is more of an organisational and production space for the Juergen Teller operation. 'Mostly here I work on layouts, models of exhibitions, editing, working on colour, organising things.' It is also home to his archive. 'But I don't photograph too many things here.' The more epic-scale commercial work and bigger fashion stories take place elsewhere in larger photographic studios. 'You don't want to have all those billions of clothes and assistants here.'

It's on those more sprawling projects where Dovile's input is particularly vital. 'I try to make things more efficient for Juergen,' she says. She started working as the creative director on his shoots five years ago. 'It was Juergen's idea, which I was very sceptical about in the beginning. But actually it's great. It's fabulous! I see my job as creating the conditions for him to achieve what he wants, and creatively, to bounce ideas off and so on.'

Is it important for him to feel at home on set? Does Juergen need to be relaxed to get the picture? 'I don't think he's ever relaxed, really,' says Dovile.

'I'm never relaxed,' concurs Juergen. 'Well – I'm relaxed now, I would say.'

'Now that he can talk about himself!' chuckles Dovile.

'If I have a big commercial job,' says Juergen, 'yeah, it does make you nervous, because you have to deliver, because there's so much money involved. At the end of the day you have to have so many outfits shot with so many bags and a shoe and this and that. And you look around and there's like a hundred people behind you.'

Given how much is riding on these commercial shoots, he takes care to choose the right clients. 'When you have a strong feeling of "yeah, they understand me" – I think that's the quintessence.' And when they don't? 'It's better to turn things down.' This may explain why he has enjoyed such longstanding and productive relationships with certain brands and designers: Marc Jacobs, Vivienne Westwood, Loewe under Jonathan Anderson and Saint Laurent under Anthony Vaccarello. That mutual trust is vital because, rather than just turning up to take the shot, he likes to consult with the client throughout the entire process, 'before, during and after, discussing it and building it; it's exciting.' From Victoria Beckham emerging legs akimbo from a big Marc Jacobs paper bag back in 2007 to Maggie Smith wearing Loewe in a humdrum back yard last autumn, his campaign images often have the power to resonate well beyond the usual reach of the fashion industry and even make the news.

Juergen and Dovile live in a house here in west London close to the studio. Does that proximity make it hard to separate their home life? Are they always thinking about work? Dovile laughs. 'Yes! But it's great. I think it's a lifestyle, not really a job.'

'That's a hard one for me to answer right now,' says Juergen, nodding towards the print-outs for the Grand Palais exhibition. 'There are lots of interviews and questions and TV and all these… dinners and stuff around it.'

One attendant aspect of the exhibition that he is clearly very excited about is the catalogue. 'I'm really happy with it,' he says, showing me a proof of the cover, which features an image of him reclining deadpan wearing only shocking pink satin shorts and multicoloured ankle socks, and holding a bunch of brightly coloured balloons. Like so many of his self-portraits where he is almost or completely naked, his exposure is presented with almost comical indifference to the airbrushed rarefaction of traditional fashion photography.

'I do these books for my own pleasure,' he continues, explaining that he wants to catalogue his work for the future, and describing the 'immense joy' he takes in working out the running order: 'You know, this image next to this one next to this one.' There's a tantalising magic to getting it right that he still can't rationalise. 'Sometimes these layouts go as easy as soft butter on bread, you know? And then sometimes you know that you really like all these pictures, and yet they don't fucking go together!' While any image might look good in isolation on the illuminated screen of a computer or phone, he notes – 'It's very seductive, this shiny thing' – placing it in a sequence on the printed page is a much truer test of its worth. Such is his love of print that he's been working on four other books alongside the exhibition catalogue. 'Dovile said, "Fucking hell, why do you need to do five books?!"'

'At Steidl, proofing pages at two in the morning!' Dovile laughs. 'But you know, then you wake up the next day and think, shit, this is really exciting. There are so many great aspects to this very hard work that we put in. And this is Juergen's biggest exhibition so far, and it is fantastic.'

So in short, yes, work does tend to bleed into all other aspects of their life together. 'But we have a natural stop,' says Dovile, 'which is our baby.' Little Iggy was born eight months ago, and family life has to come first. Last night the three of them flew back to London from Lithuania where they'd spent five days visiting Dovile's parents. On his iPhone Juergen pulls up a snapshot of Iggy that he took there: she is grinning, wrapped up in a quilted romper suit and woolly hat in a wintry forest, enjoying her first experience of snow.

'I think for Juergen, Lithuania is similar to Germany in the aesthetics and surroundings,' says Dovile. 'So he relaxes in that familiarity.'

'I mean, it looks exactly like my mom's place,' says Juergen.

Juergen moved to London from the little Bavarian village where he grew up when he was 22. 'I knew I wanted to do photography. I'd studied photography in Munich, and I was very driven.' So his desire to relocate to a city renowned for its image-makers was both logical and urgent. 'I thought, I'm just going to get in the car and drive to London. And that was it!' At that age, he notes, 'You want to get away from where you come from as far and as fast as you can.' He recalls the farewell scene outside his family's home some 37 years ago as he climbed into his car. 'There was my grandfather, my grandmother, my uncle and my aunt and my parents, all waving; and my aunt said something like, "He'll be back in three months." I remember thinking, "I'll fucking show you!" There was no way I was able to go back as a loser.'

'I left home in my early twenties too,' says Dovile, who likewise recalls a sense of determination to make a success of her new life abroad – 'otherwise everyone will laugh at you'. 'I think we share many similarities in terms of being immigrants and where we come from.' For the first eight years of her life, Lithuania was part of the Soviet Union, and she recalls food coupons and shops full of empty shelves – a stark contrast to the material abundance of New York that she experienced on a student visit. 'I loved it. I thought it had such drive and power. I thought the American Dream really did exist.' ('Not any more!' laughs Juergen.) So after leaving Kaunas with a degree in political science, she ended up living in New York for 13 years, working in fashion communication. 'I was very happy living there. I was lucky to be there as a young person. I learned that everything is possible.' ('I could never live there,' grumbles her husband. 'It's so loud!')

In 2019 Juergen had an exhibition in Tokyo which featured images he'd taken back home, where the idea of 'Germanness' was represented through the country's residents and rituals, from beer and bratwurst to portraits of himself and his mother; it was titled Heimweh, which translates as 'homesick'. Does he ever yearn for the world he was so eager to escape in his youth? 'Oh, yes! After some years away taking pictures around the world you realise, my God, you miss this other stuff.' He saw the world back home with new eyes; it was suddenly exotic. 'And I started taking pictures at home, photographing the forest… There were things I hadn't noticed before. Your senses are heightened.'

But London is definitely home now. 'It has been very good to me, for many reasons. I have a house here, I built my studio here, I have kids here – I have two other kids who have grown up now. It's a good centre to exist from, you know. The only really negative point was in 2016 when the Brexit happened.' The vote for Britain to leave the EU came three months after Juergen had finally completed the protracted five-year process of getting his studio built. 'It was really, really depressing. For the first time in since '86 I felt like a foreigner again.' The most reproduced image from his Heimweh exhibition features Kristin Scott Thomas wearing a blue hoodie styled like the EU flag, with one of the yellow stars that represent its member nations missing.

'But we remain, and London is home,' says Dovile, noting that she chose to move here after the vote in 2018. 'England is a good place; there's a lot of great things in this country.'

The mention of the Brexit vote reminds me of an interview Juergen gave to The Guardian in its aftermath, in which he said he wouldn't be able to photograph Theresa May, then the British prime minister, because 'the dislike would be too much'. Could he photograph someone he didn't like or respect?'

'Yes,' he answers immediately, and laughs. 'Like, I find that more pleasant and easy.'

Really? How so? He flashes a mischievous little grin. 'Because I can be more cruel!'

Dovile stares at him aghast. 'I don't think you're ever cruel!' she exclaims. 'That's not true!'

While Juergen's camera is never cruel, neither is it fawning: 'unflinching' is the word most often ascribed to his style. When shooting a portrait, Dovile explains, 'he takes a picture of people the way they are. And I think sometimes the problem is that people don't quite accept themselves. But if you're very comfortable with yourself, you will never have a problem being photographed by Juergen Teller. Never. Because it's not about how you look. He doesn't question whether you are good-looking or not.'

'That doesn't matter,' Juergen confirms, giving a little shrug of disinterest at the subject of conventional aesthetics. He recalls his project Go-Sees, published as a book in 1999, as a turning point in this regard: it transformed his approach to both photography and who he felt he could photograph. As one of the most feted up-and-coming young photographers of the decade, he would frequently get model agents calling up asking if they could send round their new signings, in the hope that he might choose to feature them in his work. Rather than exercise any judgement on the matter, Juergen decided to say yes to every offer that was made to him for a whole year. 'I wanted this Go-Sees project to be really democratic,' he says, and photographed all of the 462 models that were sent to him in exactly the same manner, taking a snapshot within the four square feet of his doorstep. 'It was my first conceptual project, in a way, and a really brilliant exercise for me. I learned a lot from it: how to photograph people who I liked, who I didn't care about, who probably didn't mean anything to me. But I put the same effort into making a good picture of that person. And I suddenly thought, oh, I can photograph anything now, or anybody. Before that I thought I could only photograph people who I admired, who were friends, or who I had something in common with. Like Patti Smith or PJ Harvey or Kate Moss – somebody I really liked.' In contrast, soon after Go-Sees, 'I photographed OJ Simpson, which, you know… is a very different caliber.'

The lesson of Go-Sees – that any judgement one might have regarding an individual is less valuable than the image one might create with them – has given him the patience to deal with any personality he might be assigned to photograph. 'That's something I've learned from working with Juergen,' observes Dovile, recalling how initially she would react to difficult personalities in the studio. 'Oh my God, this person's plain crazy, or really annoying, or very demanding. And he taught me to…'

'Let them be demanding,' shrugs Juergen.

'Yes, let them be who they are,' says Dovile. 'And then you take the photograph, and that's it. It's about not taking it personally. He taught me how to just be accepting of whatever, like him.'

'You know, I can eat a lot of shit,' continues Juergen wryly, reflecting on what he sometimes has to put up with. 'But at the end of the day, I'm gonna get my photograph.'

And yet… There are still some individuals who are harder to photograph, precisely because he cares about them so much. It took Juergen several years to photograph Dovile. 'I actually complained about it,' says Dovile, recalling those early days when she first became a part of his world. 'I was like, oh my God, he photographs everything. Some ant crawling on the floor; some… rock in the corner…'

'But darling,' Juergen counters, 'it took me 35 years to photograph myself!'

Sometimes the less time you spend getting to know someone, the better. Juergen mentions, by way of example, because he can see on his shelf the copy of Dazed & Confused in which it appeared, the portrait he took of Yves Saint Laurent backstage at the last couture show he attended. The designer's health was failing and Juergen was told he would have 15 minutes with him at most. 'I think I took five or 10 clicks and I thought, thank you very much – I had it, I'd got that picture. So of course, I didn't need to, you know, have dinner with him. Or sleep with him!' He laughs, but the point he's making is a serious one: the objective eye that comes with professional distance can make the job easier in some ways. 'But to photograph your kids or your mother or your wife? It's much more complex and you don't want to fuck it up.'

So he's nervous when he's taking someone's portrait?

'Well,' he says, suddenly quiet. 'I'm always nervous.'

'It's a nerve-wracking job!' says Dovile with a big laugh.

'It's a nerve-wracking business,' continues Juergen. On an assignment, he says, when the subject is not a friend or hero, he doesn't have any responsibility beyond 'wanting to do the best possible portrait of that person', which is pressure enough. But when a shoot is motivated by his own wish to document someone he loves or admires – he plucks the name of pioneering French New Wave filmmaker Agnès Varda, who he shot in 2018, out of the air as an example – 'of course I would be nervous about the work. I don't just want to do sweet, nice pictures, you know? There has to be some proper meaning behind it.'